Loitering in a shop in Aspen, Colorado, almost 20 years ago, I overheard a conversation that epitomised the paucity of credibility left in ’60s mythology. “Yeah, in the ’60s it was such an amazing time,” preached a middle-aged American in the dulcet tones of every former wannabe radical and their freak-flag flying dog. Clad in chambray shirt, pressed chinos and sporting a haircut laced enough product to detonate a small bomb in nearby Nevada, this guy represented the point where the so-called ’60s dream had come to rest: a tired, flaccid rhetorical corpse, kept on life support by the cynical celebrations of corporate interests and the rose-coloured reflections of hangers-on, shysters and the odd chemically-ravaged survivor.

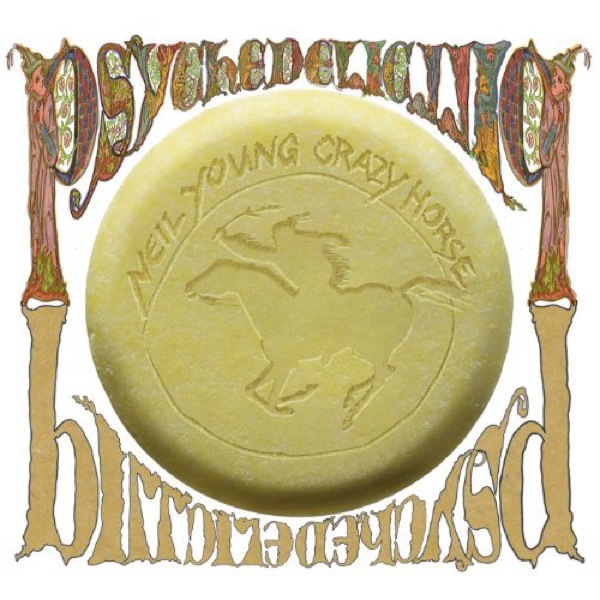

On Driftin’ Back, the opening track on Neil Young and Crazy Horse’s new record, Psychedelic Pill, Neil Young spends 27 minutes labouring through a treatise on the cultural generation into which his music was born. It’s messy and occasionally incoherent, like a grandparent meandering through a loosely-constructed story of walking to the shop and buying a bottle of lemonade with three shillings, a piece of string and a rusty nail. Young’s lyrics are idiosyncratic to the point of silliness – hip hop haircuts, Picasso computer wallpaper, spiritual awareness bought for $35, crappy MP3s. It’s the self-indulgent ranting of an old bloke who’s pissed off at the world; like the dementia-ridden nursing home resident basking in an imaginary world, Young drifts back to a time when things were better. The ’60s, man.

And that’s the subtle beauty of Psychedelic Pill. This isn’t a baby boomer’s sugar-coated memories. This is Neil Young, crotchety iconoclast walking the line between indulgence and parody. The title track – almost an ephemeral pop song in its three-and-a-half minute tenure – renders that same history in a dirty psychedelic wash. On Ramada Inn, Young spends another 16 minutes stumbling through geographical and emotional journeys. It’s The Eagles without the egos and the cocaine, The Band on the plains, America with credibility. The production is avowedly analogue, as if Young has thrown his friends in his garage, and turned on the cassette player. Born In Ontario is almost comical, a catchy ditty with Young holding court in the metaphorical music hall to a crowd of enthralled middle-aged fans.

The second disc is the same, but different. Twisted Road is autobiographical whimsy, with the Louvin Brothers and Johnny Cash loitering in the shadows. She’s Always Dancing is Young in the ’70s, freed from the shackles of Crosby’s crack pipe, Stills’ precious ego and Nash’s grating smug Britishness. For The Love Of Man is a soppy love song that starts nowhere and runs itself into cheap spiritual abandon. What the fuck is going on here? Nothing. And finally there’s another 16-minute psychedelic opus, Walk Like A Giant. And it’s here that Psychedelic Pill evolves from curiosity into greatness. Young laments the dream that’s been lost: “We were trying to save the world, we were trying to make it better/But the weather changed … and it fell apart.” But the tongue is wedged firmly in the singer’s cheek – there was never a properly formed dream, simply a series of cheap rhetorical promises that faded quicker than Jerry Rubin embracing Chicago School economics. From Jane Fonda to Jane Fonda.

The ’60s is dead, philosophically at least. But Neil Young – cantankerous, self-indulgent old bastard that he is – is still going strong.

BY PATRICK EMERY

Best Track: Driftin’ Back

If You Like These You’ll Like This: NEIL YOUNG (more than any other cheap imitation)

In A Word: Indulgent