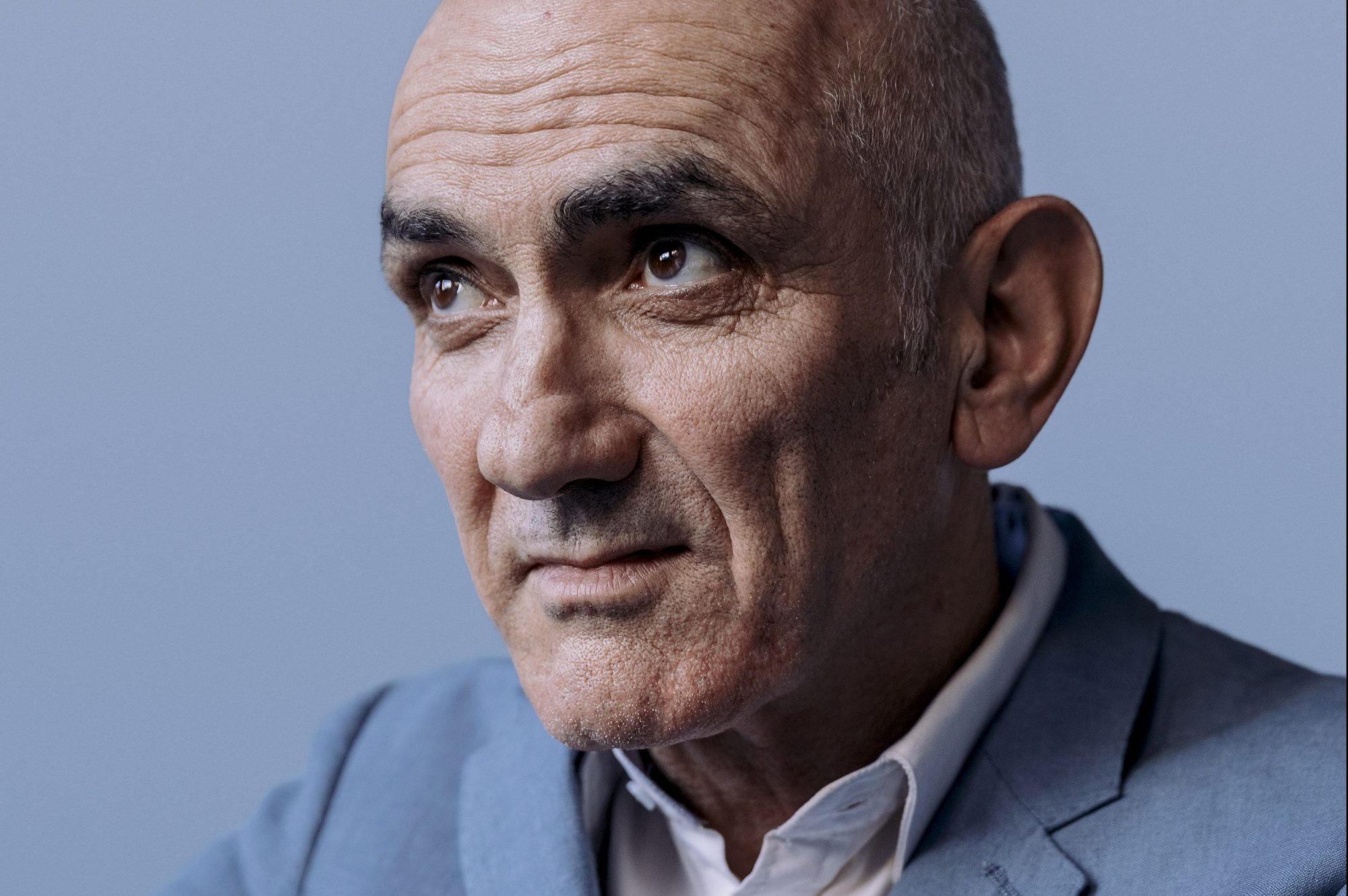

Originally released in 1997, with a second volume coming in 2008, Paul Kelly’s compilation has again been updated to include songs from the last ten years.

Unlike many recording artists in their fourth decade of activity, Kelly hasn’t slowed down. The last ten years have given rise to five solo albums, a full-length collaboration with Charlie Owen and three live albums.

This August brought Thirteen Ways to Look at Birds, which sees Kelly interpreting a number of bird-inspired poems written by the likes of Judith Wright, WB Yeats and Emily Dickinson with musical backing from James Ledger, Alice Keath and the Seraphim Trio.

Kelly’s continued songwriting and collaboration prevents any version of the Paul Kelly biography from seeming definitive, hence the twice revised and expanded Songs from the South.

“I get sick of my own habits. All writers have their own habits. I’m a fairly limited musician – I don’t have a great chord knowledge, can’t play lead guitar, don’t write guitar riffs – so working with other people or doing different kinds of records is a way of not boring myself,” says Kelly.

The range of Kelly’s career collaborators is varied and unusual. They include hip hop artist Briggs, Cambodian rock’n’roll revivalists the Cambodian Space Project, classical composer James Ledger, country songwriter Kasey Chambers, and indie pop act Little Birdy.

“I’m in the fortunate position that people will approach me about various ideas,” he says. “Thirteen Ways to Look at Birds was initiated by Anna Goldsworthy from the Seraphim Trio. She said, ‘Would you like to do something together and work with James Ledger? I know you’ve worked with him before’.

“With Briggs doing the Like A Version of ‘Dumb Things’, he said, ‘Do you want to come and sing on it?’. They played me the arrangement and I was like, ‘That’s cool, let’s do it’. They made a new song out of it.”

One of the main things motoring Kelly’s perpetual productivity is that songwriting gives him a sense of purpose.

“If I go long periods without writing something, I feel useless,” he says. “That’s what would drive me to write or go to the guitar or piano and just muck around.”

However, despite it’s self-affirming potential, making music still requires hard work and persistence. Kelly’s released more than 20 albums since his 1981 debut, Talk, largely to great critical and commercial success, but songwriting isn’t something you can unlock with a secret formula.

“Songwriting, for me, most of it’s boredom punctuated with moments of surprise when you get something,” he says. “I do a lot of doodling – I still have all these cassettes full of song ideas, and now they’re on my phone.

“I write songs on my own, slowly. They come one at a time and then I might have an idea to do something differently or work with someone else or they approach me.”

In any discussion of a musician’s collected works, there’s an attempt to simplify the career arc and encapsulate it within a linear, cogent narrative. In the annals of Australian music history, Paul Kelly is a living icon, but he’s not too concerned about how his new releases will alter the shape of his career biography.

“I saw Tim Minchin once give an address to a group of university students – he was being given an honorary degree and he made this great speech. He [said], ‘Don’t worry about the big dream, just do the thing in front of you well’. I just try to do the thing that’s in front of me.

“I come from a big family. I have children, grandkids, friends, I’m part of a footy club. That’s more where my sense of self lies, amongst that. The songs are sort of something else. Once you make them and record them and put them out, they travel away from you. The songs do their own thing.”

The newly-revised Songs from the South is out on Friday November 15. Check it out via streaming services.