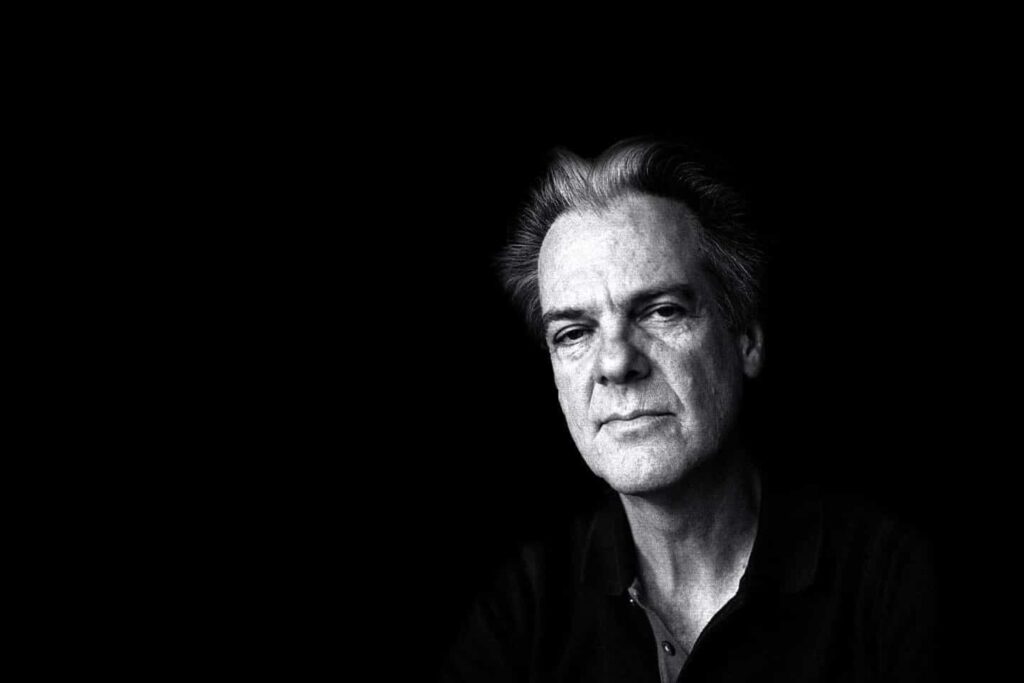

Mutiny definitely were very punk before getting very folk. “We were sort of a punk scene offshoot,” begins guitarist and founding member Greg Stainsby. “We were at the tail end of the ‘80s thrash scene. We hung out with some political ‘80s thrash bands. But we took to acoustic guitars and medieval themes. We were the folk band on the thrash bill,” Stainsby laughs.

“We found ourselves in Fitzroy in about ’92. A whole new music scene was taking off at that time. It was there where bands did what they wanted. We went from the thrash/punk thing and went in our own direction.”

Within two years, Greg with his “folk punk for punk folk” octet ventured to Eastern Europe. Through exploring this newly-freed continent, arcane Balkan melodies began to trickle through a very Aussie Mutiny.

“What people liked about us is how Australian we were,” Stainsby recollects. “Why emulate overseas bands? Why not embrace our own sound? We did get more deliberately Australian, but we were also influenced by Eastern European gypsy sounds as well. We got two things: an Australian theme and an Eastern European vibe.”

Today, Eastern Europe is a playground for the wealthy and famous. Contrasted to ’94, die-hards built their musical cities on a punk-style DIY philosophy.

“There were these bars that were run by squatters,” Stainsby recalls. “People had taken over the empty buildings, especially in places like Berlin. They were just running these great venues and living in these buildings. There was a whole circuit of these throughout Europe where you could play. It was quite amazing. We went to Croatia in ’97, after their civil war. We went to the Czech Republic, Slovenia. When we were going off the beaten track a bit, people really appreciated us making the effort.”

On paper, their release schedule looks scarce: three long-players and three EPs. Mutiny’s tunes soaked the walls of pubs and beer halls instead. Their 22nd anniversary record, Drink to Better Days, commemorates a career lived confidently on the road. Naturally, some of their musical “babies” didn’t fit between those flat polymer walls.

“[Tracks] were chosen from over five releases,” Stainsby explains. “We tried to get the best tracks of each one. It was hard, but some songs stuck out because they sounded better.”

Stainsby and the band carefully plucked tracks wholly representing their double decade career, though Drink’s got “nothing from our [first] tape, which we’re quite embarrassed by,” Stainsby sheepishly chuckles.

“We chose a couple from our mini-album Any Way You Can and our EP Bodgy Tatts to show where we were at and what we were doing,” Stainsby reveals. “We chose a lot of tracks from the Rum Rebellion period, as we had a sound we were happy with.”

Back in ’91, the music scene was a totally unrecognisable beast compared to today. Different suburbs had their own niche. For example, Richmond was the metalhead’s haunt. The clubs and pubs this generation’s grown to love didn’t yet exist. If a handful of moaners get their way, these venues could sadly return from whence they came. But is today any different than when Mutiny grew up?

“It is pretty bad now that this keeps happening,” Stainsby says on threats to live venues. “We were lucky that we saw an expansion of opportunity, with venues growing in the mid-‘90s, in suburbs like Fitzroy. It became a cultural hub. It is pretty annoying when someone moves in and complains when the venue has been around for a long time. Even so, compared to then, there’s still a lot more going on now.”

BY TOM VALCANIS