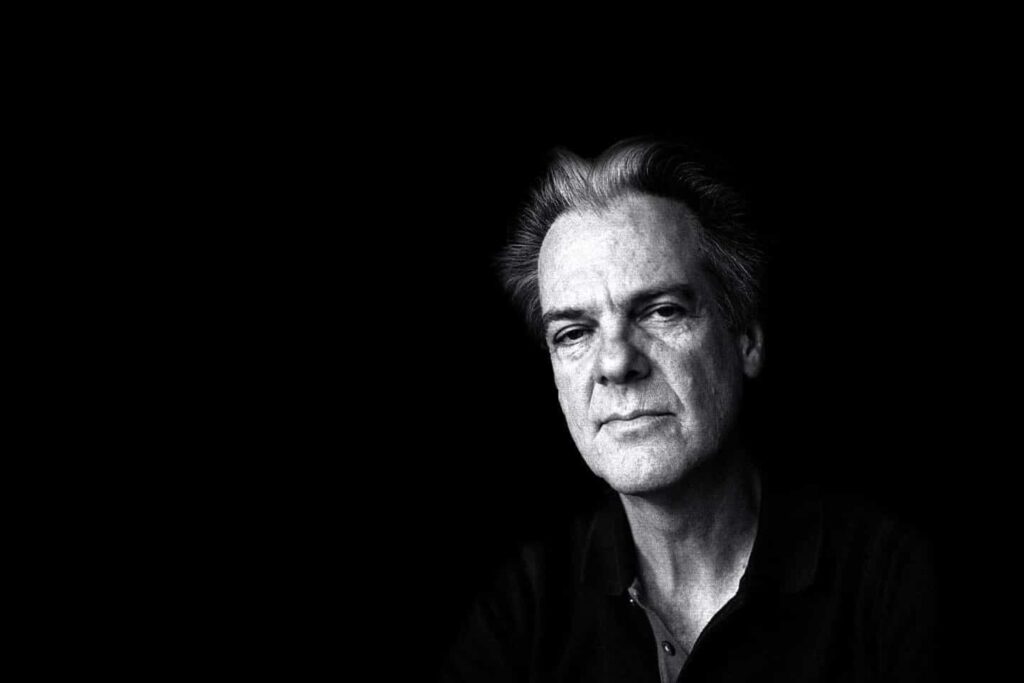

Mention Justin Townes Earle to many folks in the music industry and watch their eyes light up. He’s long been a musician’s musician, but one who’s managed that rare engagement with a fanbase as widespread as it is disparate.

Kids in the Street marks his eighth record in ten years (the man is nothing if not prolific), and like most of his records, it showcases a range of tones and themes; this time, though, it comes wrapped in a strong sense of nostalgia, evidenced most clearly on the album’s title track. Here, Earle talks to us of words and burglary.

“There’s always that one [song],” Earle explains. “It’s usually the first song that I start to write that triggers the domino effect that triggers the record. All of my records have worked that way. Over time I’ve gotten more and more into the concept, but there’s always been some kind of conceptual thread through them.

“It’s the same thing when a song’s finished, there’s no real way of saying when that time is, you just get a feeling when it’s right. I do find it important what comes first, though, and then what will follow. It’s almost like a let-down feeling when the song’s finished. I have an uneasy feeling, I question if it’s actually finished. But I’m a very slow, very deliberate songwriter, so if somebody broke into my car and stole one of my notebooks, they might maybe have a complete version of a song, but it’s going to be full of rewrite after rewrite after rewrite. I do a lot of toying with the shape of phrases, with time, things like that. No song comes overnight. That’s very rare.”

Being friends with a musician who did indeed have her car broken into and experienced the loss of both her guitar and notebooks, I hazard that such an awful scenario might not be that outlandish.

“I’m pretty protective. I do make sure that they stay in a safe position. There was a song called Kids in the Street that I wrote when I was 18 years old. It wasn’t a good song, but I still had the blueprint from that notebook that I’ve carried around since then. Whether I’m arrogant, I don’t know, but I still see everything I’ve done as a natural progression to what I am now. I don’t regret a single record I’ve made. So, I don’t know what I’d do if someone did get off with [my notebooks]. But I mean, someone would have to get off with a lot of legal pads in order to get way with a whole record of my scribbling. I’d lose my mind. I’d want to kill someone. You steal a songwriters song, that’s no trial, no nothing. You get taken out and shot.”

Earle has always been a rather nomadic musician – having once interviewed his father Steve, he referred to Justin as believing in ‘geographic remedies’ – and while he now calls Oregon home he has lived in Galway, Nashville, New York, Chicago, and has toured his music across the globe. He’s certainly no stranger to Australian shores, and this wanderlust has had a tremendous impact on his writing craft.

“I read a lot, I think a lot of what I read comes out in what I write. I pay very close attention to the way that people talk in certain places. I’ll get made fun of, because after being in a certain place for a length of time I’ll start saying things the way locals would, just because I’m fascinated by that.

I see that as just another way to be able to rhyme something. Now, in the past, say I wanted to write a song that involved Melbourne, I would only have been able to rhyme it with born. But now I’ve got Melbin, which gives me a whole new rhyme scheme and a different way of looking at how to use it. Paying attention to the way locals say things has always been a big part of understanding language, and ways to use it.”