Please Kill Me , Legs McNeill and Gillian McCann’s oral history of the abrasive edge of American rock ’n’ roll centred in New York City, offers a salacious narrative of the genesis and evolution of punk rock. Tales of drug excess bleed into escapades of sexual perversion, egotistical wrangles and mindless fuck-ups.

Please Kill Me , Legs McNeill and Gillian McCann’s oral history of the abrasive edge of American rock ’n’ roll centred in New York City, offers a salacious narrative of the genesis and evolution of punk rock. Tales of drug excess bleed into escapades of sexual perversion, egotistical wrangles and mindless fuck-ups. The chapters devoted to The Stooges fall into two basic categories: the early years, when Michigan natives James Osterberg, brothers Ron and Scott Asheton and Dave Alexander supplanted the wild-eyed wonder of psychedelic rock wave with the hard-nosed industrial edge characteristic to Detroit youths; and the second, darker period, when the band’s creativity was sapped by heroin addiction, industry indifference and dysfunctional personalities.

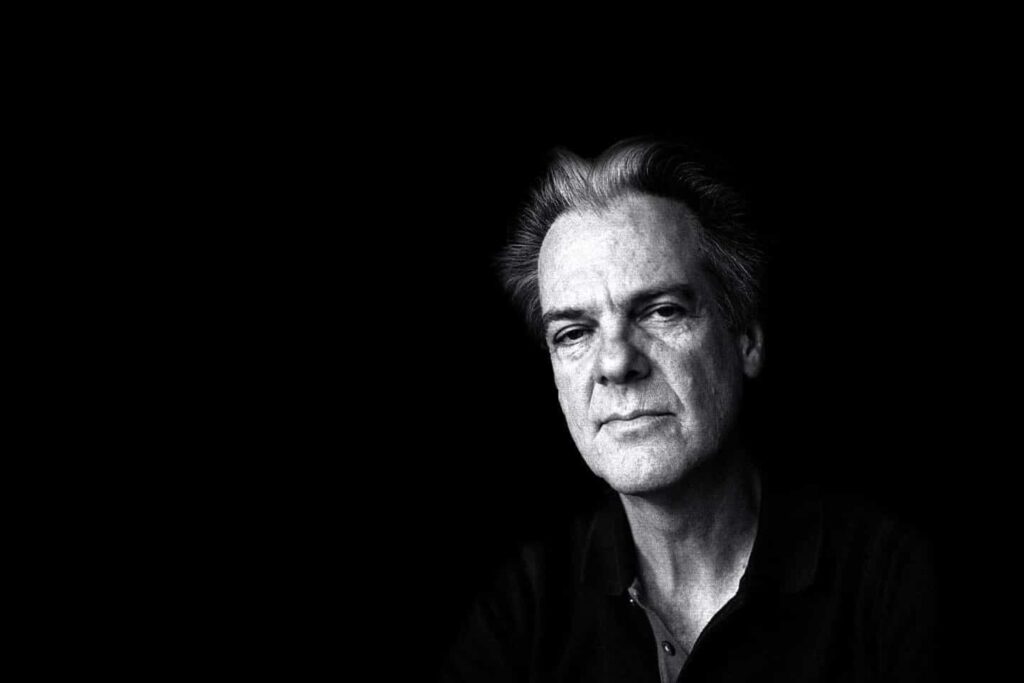

It’s in the second party of The Stooges journey that the name James Williamson first appears. Legendary photographer and scenester Leee Black Childers’ (yep, Leee with three e’s) disdain for Williamson is palpable; Kathy Asheton describes Williamson as a ‘black cloud’ descending on the group. Almost forty years after he joined The Stooges, and thirty years after he took leave of the music industry for a successful career in the electronics industry, Williamson isn’t noticeably bitter about such assessments – though he has made an effort to rehabilitate his reputation. “I think I have done that at various times recently when I’ve been giving interviews,” Williamson argues. “Please Kill Me is total rubbish – it’s poorly researched; it’s complete hearsay from people who either didn’t know me, or didn’t like me.”

Growing up in Detroit in the 1960s, Williamson’s life seemed headed for the same skid row territory that engulfed many of his contemporaries. At age 16, his step-father gave him an ultimatum – cut your hair, or go to a juvenile home. Williamson chose the path of greatest resistance, and his long locks remained. Having known Iggy and the Asheton brothers through local bands (including The Chosen Few, in which both Williamson and Asheton played at different times), Williamson joined The Stooges on guitar in the aftermath of the release of Funhouse. Until the release of recent live bootlegs a couple of years, the Asheton-Williamson twin guitar line-up remained the stuff of fading memory and Stooges mythology.

Williamson agrees it’s disappointing the five-piece Stooges never made it to the studio. “Very much so,” he says. “We thought we were going to record. When I joined the band it was six months after Funhouse. We thought we’d do a third record with Elektra, and I was introducing new material,” Williamson remembers. Tired of the band’s behaviour and unimpressed by the new material, Elektra declined the option to make a third album. “We had some record executives come over and they couldn’t deal with it,” Williamson shrugs

With no record deal, The Stooges folded, entering a hiatus and Iggy and Williamson headed to the UK at the instigation of David Bowie. Faced with a deficient backing band, Iggy and Williamson called up the Asheton brothers and invited them to travel across the Atlantic. “It didn’t take long for us to realise that the musicians we auditioned weren’t compatible, so we decided to bring the Ashetons over,” Williamson recalls.

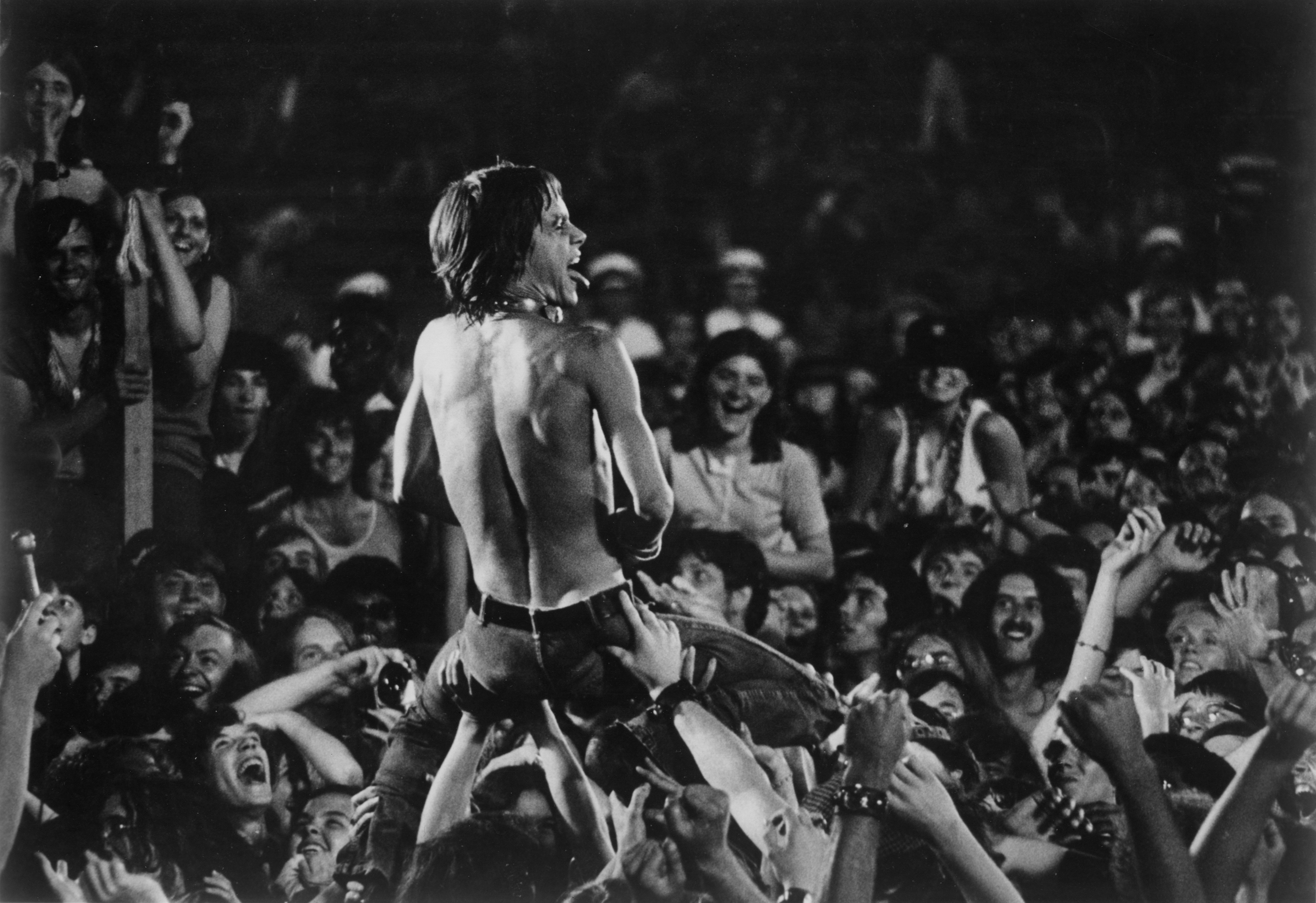

The result was Raw Power, a tangibly different album to the previous Stooges record, and a crucible for the English rock ’n’ roll scene, at that time taking the first ginger steps from glam to punk rock. But it was Metallic KO, recorded at the violent end of The Stooges’ existence, that captured the greatest attention in the nascent English punk scene. “Those shows were pretty dangerous, yeah,” Williamson smiles. “We didn’t have enough sense to leave the stage. I think it [Metallic KO] romanticised and glorified the violence in the show. Maybe a lot of things in the punk scene might not have happened without our part.”

After the implosion of Iggy And The Stooges, Williamson and Iggy collaborated on Kill City. It’s also been suggested the 1977 release of Kill City was nothing compared to the original masters… Williamson, however, doesn’t agree. “I was totally involved in all of it,” he says. “The original masters were used in the early release – the early tracks just weren’t finished. When Greg Shaw approached me he asked me to go back and finish the tracks in the studio, which I did.” In early 2010 Williamson was given the opportunity to remaster Kill City for its re-release. “The multi-tracks were still there, but the stereo tracks weren’t,” he says. “But I’m very happy with the way it turned out.”

By the time of Kill City’s release, Williamson’s focus had moved from playing to production, and he was tired of Iggy’s unreliability and antics. Williamson’s last musical dealings with Iggy had been the recording of Soldier In Wales in 1980, an unhappy event and unsatisfactory outcome from everyone’s perspective. Paul Trynka’s biography of Iggy describes an agitated Williamson prowling around the studio with a gun and a bottle of vodka. “What a loaded question!” Williamson laughs, when asked if the stories are true. “What happened with Soldier is that we’d finished (1970 album) New Values just before, and the record label wanted a more punk record – we were always out of step with record company expectations,” Williamson recalls.

“So the record company put us out in Rockford with these punk rock musicians. Early on I wasn’t too enamoured with those musicians. It seemed like a recipe for disaster, so I focused on the technical things. And it went on, the more unhappy I was, and the more unhappy I was, the worse it became,” Williamson explains.

Iggy Pop’s Dum Dum Boys from The Idiot had already noted that James was “going straight”, and Soldier was the last straw in his dealings with Iggy. Williamson subsequently went back to college, started a family and began a career in the electronics industry that saw him reach the heady heights of corporate America. When Williamson returned to The Stooges’ fold in 2009, it came as a surprise that this mild-mannered businessman had such a colourful history. “Not many of [his business colleagues] knew,” Williamson chuckles. “It’s been a surprise for them. Maybe I could’ve been more open at the time, but people get used to it and are comfortable with it. And they get to live vicariously as a rock star,” he laughs.

Ron Asheton’s death in January 2009 was the catalyst for Williamson’s reuniting with Iggy. “He called when Ronnie died,” Williamson says of Iggy. “He wanted me to fill me in with the funeral arrangements. When someone dies like that, it makes you talk. So we started talking about playing. At the time I was still working at Sony, so it wasn’t really an option. Then I took an early retirement and the opportunity to play in the band again arose,” Williamson explains.

Now into his 50s, with his rabble-rousing days well behind him, and Williamson is enjoying playing alongside Iggy again. “With us you can’t really separate the two,” he says. “We’ve known each other since our 20s. If you separate us out we’re good musicians, but if you put us together it makes something special.”

IGGY & THE STOOGES headline the BIG DAY OUT along with Tool, Rammstein and heaps more at Flemington Racecourse this Sunday January 30. All info through bigdayout.com.