“There was a tiny, little metal phase,” confesses Gawenda. “It wasn’t that tiny,” Preiss chortles. “I remember when Husk got his first electric guitar, which was a BC Rich. It’s a metal guitar and it’s set up for shredding and playing fast. I used to go around there and Husk and my big brother would be working out Guns N’ Roses and Metallica solos – Enter Sandman, that kind of thing. I could not have been more jealous.”

“But that phase didn’t last long,” Gawenda interrupts, trying to regain some ground. “That guitary, wanting-to-shred thing lasted a couple of years and then I went back to Leonard Cohen songs.” Gawenda then dobs and lets slip Preiss’ Mum (together with most ladies of the time) had a little thing for Ricky Martin. “And you loved it,” he says gleefully of Preiss, but is made to recant immediately.

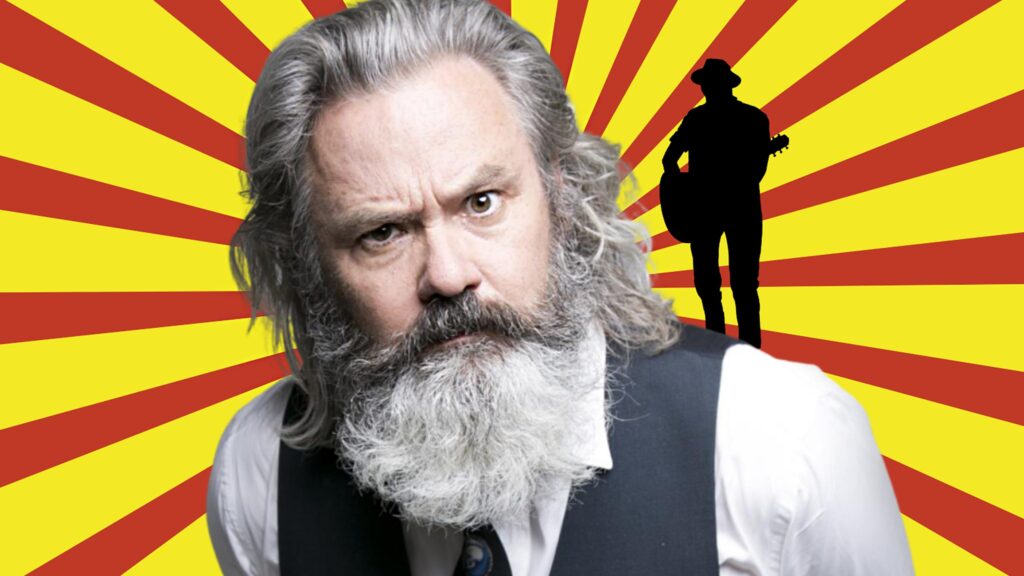

The boys have made no secret of the fact they’re influenced by singer/songwriter greats. Husky draws on Dylan, Crosby, Stills & Nash, The Beach Boys and, of course, Cohen. They’ve been life-long loves and despite a few musical lapses, it’s clear they’ve always had pretty mature musical tastes. For Gawenda and Preiss, it was the stuff playing in their folks’ cars when they were kids and they’ve always connected with them. “They’re artists that you grow with as you develop,” Preiss explains. “But I loved Dylan, Neil Young and Cohen as a kid. I loved them then and I love them in a different way now. I guess we were lucky to have good musical influences early on – good records playing in the lounge room.”

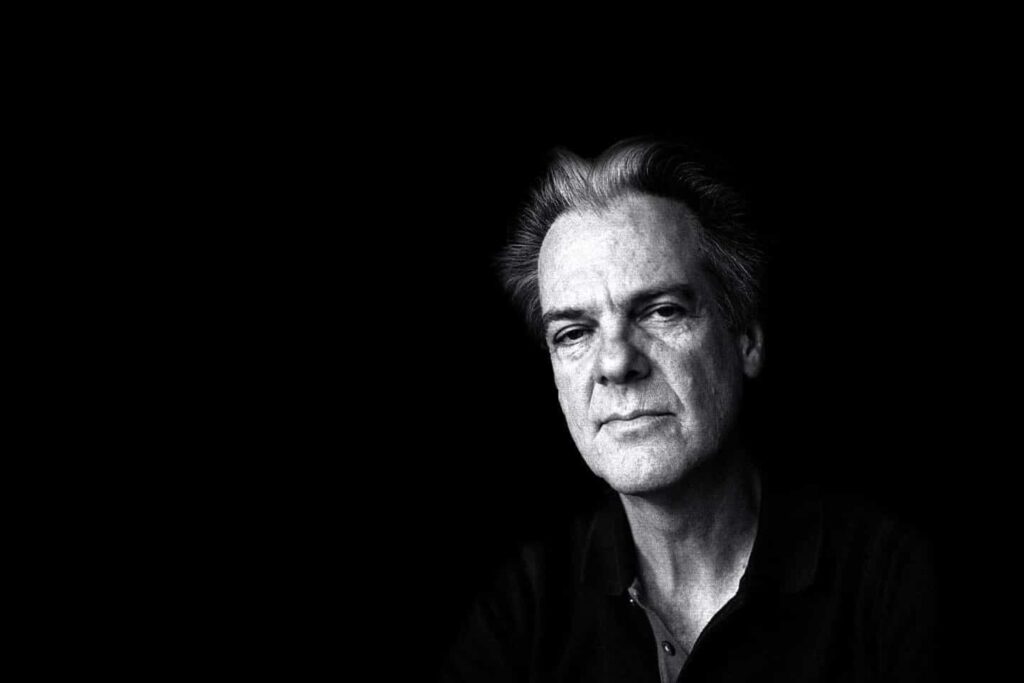

There’s actually a lot of discussion about Cohen, the golden-piped 80 year old, partly because he’s releasing his 13th studio album that day and also because Gawenda was reading bits of his last novel Beautiful Losers in his local café during the recording of Ruckers Hill. To be clear, neither Gawenda nor Preiss compare Husky to Cohen or any of the other greats listed above, but they do provide a yardstick of sorts for their song writing. “If the song’s not taking me away, I’m thinking, ‘Man, what’s the fucking point?’ when guys like them can make this kind of music and these kind of songs,” says Gawenda. “On the flip side, you don’t have to write the greatest songs ever and make the greatest albums. You can just aim to do something good and move people. Most of the time, I feel like if we are achieving that at all, we’re achieving plenty. I’m still jealous of Leonard Cohen though. He’s a once in a century kind of guy.”

Steering away from Cohen (who we could chat about all day) and back to Husky recordings, Gawenda and Preiss describe the experience of recording their debut album Forever So as unique, insofar as they’d complete creative control over the process. They recorded it at Gawenda’s rented Fitzroy abode in a shed out the back, which also meant they weren’t fettered by time or money constraints. So, if holding the reins is something the band values, how did the experience of recording Ruckers Hill compare? “I think we did have the same degree of creative control,” reflects Gawenda. “The difference this time was that the label and other team members invested in what we were doing. That creates some pressures and expectations that we hadn’t dealt with before, but, essentially, we were totally in control of what we were doing and I still feel that the greatest expectations and pressures came from ourselves, as they did on the first record.”

Similarly, the fellas’ve said they didn’t write Forever So with any particular audience in mind and it’s equally true this time around – the band’s musical integrity is not up for grabs. “You’ve got to answer to yourself on all of these things,” says Preiss. “In 20 years time you want to feel like you created something you’re happy with. When we made the first record, we never really had any expectations around how people would receive it. I was actually very surprised that it was well received. I feel like I don’t have a choice about it. You have to set those standards for yourself. There are certain things that you don’t compromise and authenticity is one of them.”

“It can be a little bit like chasing shadows with a flashlight though,” qualifies Gawenda. “If you’re trying too hard for authenticity – that’s not authentic. You need to let go of trying too hard for anything. Often, it’s best just to let go of all of that stuff and just write and record.”

Did they achieve that with Ruckers Hill? “An album’s a snapshot,” reflects Gawenda. “Forever So was a snapshot of three years ago and Ruckers Hill’s a snapshot. If the album sounds different, that probably has more to do with the fact that time has past and life has changed and we’ve read different books, listened to different music.” “And spent time touring,” Preiss interjects. “That has an effect on the things you write and what you want to do going forward.” However, they both agree it can be a detrimental to their mental health. “In other words, we go crazy sometimes,” Gawenda laughs.

Although they say you should never work with mates and family, Preiss and Gawenda are an exception to the rule. It’s obvious not only are they good mates but their shared history is an advantage. Preiss has a nice spin on it. “I feel that it makes at least parts of working together easier,” he reflects. “The best example I can think of is when you’re touring, because when you’re away for long stretches and you’ve got family there you feel like you’re taking a bit of home with you and there’s a lot of comfort in that for me.

“If someone had said to me when I was a kid that I’d get to tour and work and play music and do all of the things we’ve done together with my big cousin, I would have been the happiest little kid in the world. It’s nice to remember that.”

This leads into a discussion of the shit they used to get up to as kids, which is definitely worth recounting. “We were very into action movies,” Preiss admits. “There was a lot of acting out Steven Seagal, Van Damme and Young Guns. I remember feeling very stiffed that I was always Lou Diamond Phillips and only got this little dagger, while Husk was Emilio Estevez and Benj, my big brother, was Charlie Sheen and they had the guns. I never got the gun.”

“It wasn’t so much a musical thing,” reflects Gawenda. “Although me and your brother did the Beat It fighting dance sequence. There were a few months there were we did it every morning. We used to go and get forks from the kitchen – we weren’t allowed to do it with knives.”

BY MEG CRAWFORD