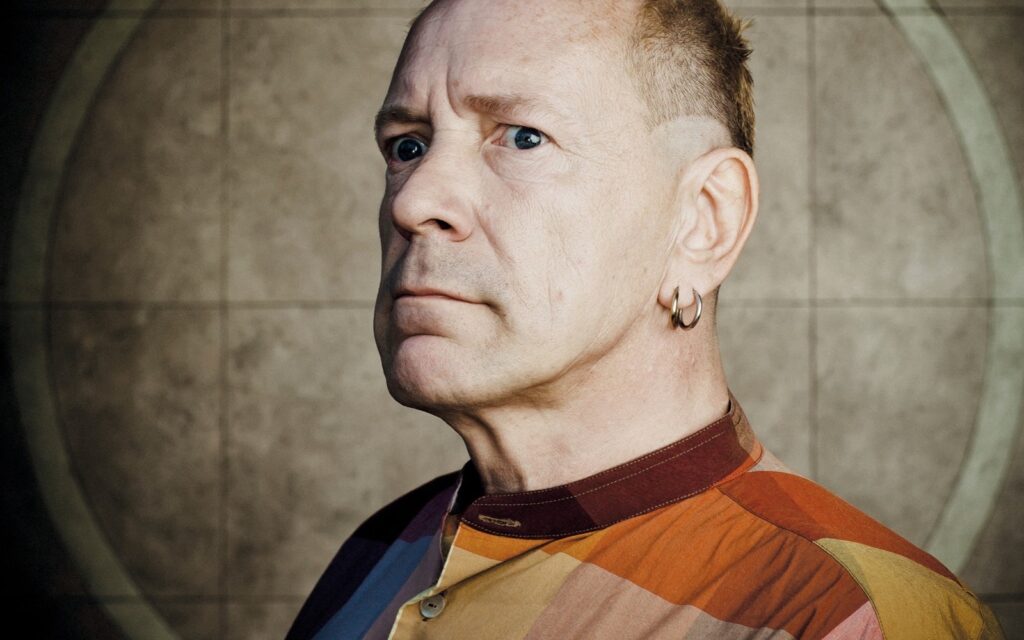

He’s been making music for quite some time. At the age of 15, Rosenberg began recording songs in his bedroom that were extensions of whatever music he happened to be listening to at the time – whether it was Michael Jackson, Billy Idol, Def Leppard or videos on MTV. “What inspired me [initially] was just the people making records, and that’s the only reason!” he exclaims. “I didn’t understand how there were so many artists out there, making so many records.”

His ultra-lo-fi and experimental recordings evolved as time progressed. “The songs just kind of mutated, and shit got heavier and heavier,” he laughs.

It seems that what Rosenberg was truly after in his recordings was, in a sense, a deconstruction of the popular music that permeated his upbringing. “I was always very cognizant of what I didn’t want to do – I always wanted to be different and so [my music] wasn’t so much an amalgamation of what I like as much as [it was] just a stage of what to avoid,” he continues. “I had this feeling, at a very fundamental level, that I wanted to write the most boring song, the [saddest] song; I wanted to write stuff that didn’t matter, something that I could just cling to.

“I basically got my sound with a combination of using my ‘mouth drums’ which was essentially an extension of my mouth, and then I had a bass guitar and I’d do my melodies with that, so it was all a very, very basic groove. The sound itself was very pedestrian; I wanted to make a pedestrian version of everything that might be considered ‘pop’. I wanted to put across a very, very weak and satanic world. You know, something that wouldn’t be encouraged by anyone. Something that’s more of a warning sign! I wanted to scare people a bit!”

Whether or not Rosenberg’s compositions actually scared people is unknown. But they can certainly be described as challenging. Tracks such as L’Estat (Acc. To The Widow’s Maid) and Round And Round, whilst certainly of higher quality than his earlier recordings (which were as “lo” as lo-fi can get), still provide a challenge to the casual listener with their avant-garde je ne sais quoi and an anything-goes, individualistic attitude.

When this writer posits that his music is an example of the artist staying true to his self and not watering shit down to the lowest common denominator, he is quick and vehement with his reply.

“I completely disagree,” he says bluntly. “You don’t have to stay true to yourself at all – there’s nothing there! I mean, what’s ‘true’? You can try things out, and if you fail then you failed. So what, if you have a few duds? If you have one good song, you should be happy. It doesn’t matter.

“Staying true to yourself really has much more to do with me, and my ego, and my peccadillos and what I have to say. I mean, those are the things I tell myself, and those are the things that are important to me, and they have very little to do with what people find they think about my music or what is ostensibly special about music. You can’t do wrong if you continue to make music. People might ridicule you at some point, but if you just continue doing it without letting people get you down, then you’re going to have the last laugh, you know?”

And when it comes to last laughs, Rosenberg has emerged victorious. “I think I was always ready to share my stuff with audiences,” he reveals when I ask him about his transition between going it himself and then sharing the stage with a proper band. “In the beginning, there were no hostile reactions; it was an extremely encouraging environment, and I thought I was good at [performing solo], so that’s why I kept on doing it. But that was just on the local level, and about four or five years before I got signed. So I was probably at my most groundbreaking and my most confident, just doing the ‘karaoke’ thing.

“And then as time went on, I started to strip down [the music] more and more; suddenly stage-fright started to rear its head and I started to put myself into very, very compromising situations by actually playing in front of people and not being prepared and not having a setup that can be easily described as functional – and then going on the road with that [setup] and having to weather all sorts of humiliation and discontent from people who were curious about us.

“Playing with different lineups, it was just diminishing returns, and it was less people showing up; and it was people thinking, ‘I just can’t get into this.’

“I had to find a way to enjoy it,” he says after a brief pause, “and I realised what I had to do was to get a band of committed musicians and make sure it was an outfit that over time could commit and stay true to the music, the songs and the arrangements; having a band that was capable as well as prepared.

“It was all just a very gradual process,” he continues, “and when I did those things I got a band together so that we could make music, that I could enjoy my concerts and get to the point where I could have a real band and real chemistry onstage and get on a record label! That was cool! We did it in two years and – yep – mission accomplished.”

BY THOMAS BAILEY