John Cale is a genuinely intriguing human being, albeit under the contrived circumstances

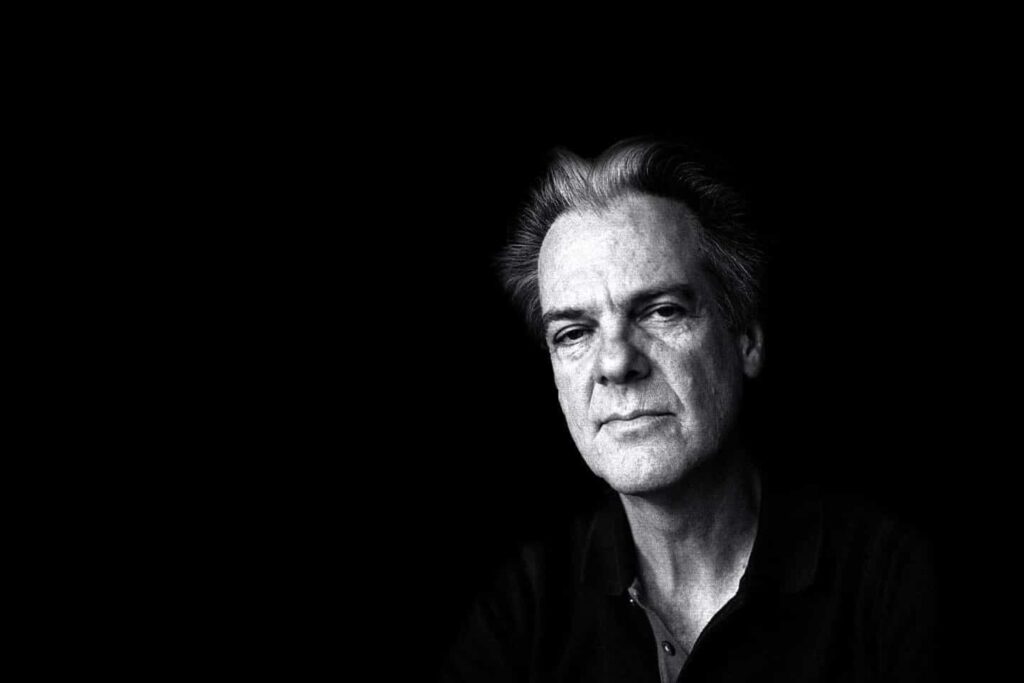

John Cale is a genuinely intriguing human being. Even when you’re engaged in notional dialogue with the legendary musician, avant-garde composer and producer – albeit under the contrived circumstances of a telephone interview – you get the sense that he’s operating on a cerebral plane you’ve never even comprehended exists. So when Cale suggests that even he hasn’t quite worked out what personal meaning lies deep within his 1973 solo record Paris 1919 , it’s entirely understandable. “Some of the lyrics on Paris 1919 are still opaque to me ,” Cale muses. “Some of them I’ve decoded, but sometimes I think ‘What the hell is that all about?’”

By the time he entered the studio with producer Chris Thomas to record Paris 1919, Cale had already racked up an impressive resumé. Having moved to London from his native Wales to study classical music in the late 1950s, Cale headed to New York in 1963 where he soon found common artistic ground along side John Cage, Le Mont Young and Aaron Copland. He also met former jingle writer Lou Reed and formed The Velvet Underground in 1965.

By the late 1960s Cale’s relationship with Reed had turned sour, and he left to pursue other interests, including producing The Stooges’ seminal debut record in 1969. Cale embarked on a solo career, releasing Vintage Violence, Church Of Anthrax andThe Academy Of Peril in the early 1970s. In 1972 Cale signed with Reprise Records and teamed up with Thomas to record what would become Paris 1919.

In his subsequent solo outings Cale would return to the improvisational style he’d embraced early in his musical career; for Paris 1919, however, Cale already had a selection of songs, the majority of which reflected his sense of personal and geographical dislocation. “All of the songs were written before I went into the studio,” Cale recalls. “After that record the songs were improvised a lot more, but with Paris 1919 all the songs were written in seclusion.”

Cale describes the thread running through Paris 1919 as “the perspective of someone stranded in the desert … a Welshman landing in the desert”, and consistent with his own state of mind. “I didn’t realise until later just how personal the record was,” he adds. “I had all these memories from my childhood, and there were a lot of problems in the world at that time.” Cale cast an eye toward the historical narrative, and identified the peace process that followed World War I – which begat the economic and political problems in continental Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, followed by World War II and the subsequent division of Europe along ideological lines – as the root cause event. While he figures the basic idea of the record wasn’t widely understood by his audience at the time, “there was enough symbolism in the album to read into it… in the amalgam of icons you get the semblance of the idea,” he nods.

The songs of Paris 1919 are replete with iconic figures of the time – including Graham Greene, Enoch Powell – matched with images from Cale’s Welsh childhood. “I think with the Enoch Powell reference, people would have only got the reference if they lived in the north of England,” he notes. “Powell’s infamous ‘rivers of blood’ speech [in which Powell recited apocryphal scenarios resulting from post-war immigration] was made in a private meeting, and only came to light after someone reported the speech to a journalist.” As for the Welsh references, Cale dismisses any sense of romanticism toward the land of his birth. “I wasn’t trying to be romantic – I was trying to be realistic,” he points out. “I suppose I missed it, but there was nothing there for me.”

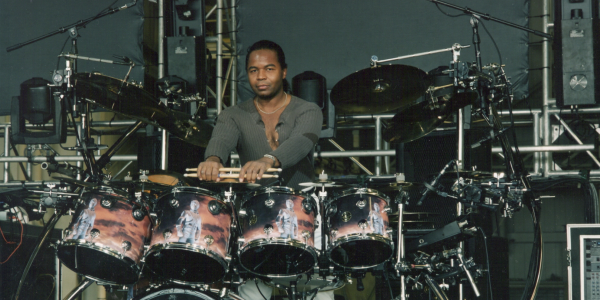

He also pays tribute to the production assistance of Thomas, with whom Cale had not worked previously. “I hadn’t worked with Chris before that record,” he explains. “Chris spent a lot of time listening to the music over and over – I didn’t know what he was listening to. I was just hearing the songs with all their imperfections.” Thomas had been suggested for the record by Reprise’s parent company, Warner; it was also via Warner that Cale came to work with members of LA boogie band Little Feat, including the late Lowell George, Billy Payne and Richie Hayward.

“They were signed to Warners, and someone asked Lowell George if he’d be interested in playing on the record. He said yes, and the rest of the guys followed,” Cale remembers. His admiration for Little Feat only grew after working with them. “They played working class music,” Cale muses.

It’s clear that he’s an artist with a perpetual interest in exploration and re-invention. In the last decade Cale has waxed lyrical about the artistic importance of hip hop performers. “I learnt a lot from guys like Snoop Dogg,” he admits. “Some of that music is ground breaking – there’s some real imagination in there.” It was with some surprise, then, that Cale accepted the offer to revisit Paris 1919 and perform it in its entirety. But with John Cale, it seems, nothing is predictable. “I don’t mind going back to it because I knew it would sound different anyway,” he argues. “The lyrics now make more sense to me than they did at the time.”

Cale has since performed Paris 1919 with orchestras around the world, including in his native Wales, Paris and Italy. Each time he has played the record in a different location, and with a different orchestra, Cale adds, the album’s performance changes. “All of those orchestras are different,” he nods. “Every time we’ve done the record, we have managed to orchestrate another song.”

On October 16 Cale will perform Paris 1919 accompanied by the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra as part of the Melbourne International Arts Festival. In addition to Paris 1919, he will undertake a spoken word performance, as well as participating in the Seven Songs To Leave Behind event at the Myer Music Bowl alongside other artists including Rickie Lee Jones, The Black Arm Band and Sinead O’Connor.

The Seven Songs to Leave Behind event involves each performer playing their first composition, the song that switched them on to being a musician, a song from Leonard Cohen, a song to share with another, a song that they wished they had written, two songs of their own and a song to leave behind. Cale names the Winter Song (recorded originally by Nico) as his first song, but is coy on the song he wished he’d written. “I’m still debating it,” Cale says, “because I have to think about all the songs that are in the list.”

The legendary JOHN CALE plays a one-off live performance of his 1973 masterpiece Paris 1919 at The Arts Centre, State Theatre on Saturday October 16. He’s also doing a qna session called Noises In My Head at The Arts Centre, Fairfax Studio on Tuesday October 19 at 7.45pm. Then he takes part in the Seven Songs To Leave Behind shows, at the Myer Music Bowl on Saturday October 23. All info and tickets through melbournefestival.com.au.