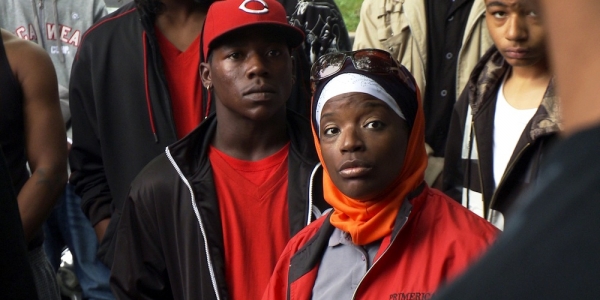

The same can be said of Ameena Matthews. Now a Muslim and mother of four, Matthews is the daughter of Jeff Fort, Chicago’s most infamous gang leader bar Al Capone, and was once a gang enforcer herself. Or Cobe Williams. This jovial and jocular man has done three stints in jail for drug-related charges and attempted murder. Nowadays, however, these three are drawing on the experiences of their chequered histories to help prevent young people in their communities from making similar mistakes. Their job title? Violence Interrupters.

“It’s true that all of the interrupters in some fashion have lived a life in that world. They’ve been in ‘the game’,” says documentary-maker Steve James, who spent 14 months filming their work in Chicago’s most impoverished and bellicose suburbs. The result is his latest film The Interrupters.

Violence interruption is an initiative of Ceasefire, an organization started by epidemiologist and physician Gary Slutkin, who had previously spent 10 years battling infectious diseases in Africa. The philosophy behind Ceasefire is somewhat unorthodox — Slutkin believes that violence spreads much like AIDS or tuberculosis. Target the most infected, and you can stem the infection at its source. Stop one murder, and you can stop the retaliatory chain reaction that follows in its wake.

Therefore, CeaseFire does not address the problems that cause violence, such as poverty, lack of quality education, racial ghettoisation or gun culture. They do not try to get kids out of gangs or off drugs. Instead, they simply mediate conflict before violent incidents take place. While some may view this as a band-aid solution, CeaseFire’s success is in part attributable to their non-judgmental approach. A recent study showed that in six of the seven neighbourhoods examined, CeaseFire’s efforts had reduced the number of shootings or attempted shootings by between 16 – 27 percent.

James first visited these communities in 1987 when he began filming the critically acclaimed Hoop Dreams, which follows two African-American teenagers hoping to make it to the NBA. But according to James, it is sometimes difficult to see the progress that’s been made in the nearly 25 years interim.

“Murders are down in those communities and in Chicago as a whole. When we first started shooting Hoop Dreams, it was really probably at its peak and that’s because the crack epidemic was at such a level that a lot of people feel like that spurred a lot of the violence and a lot of the murders, and that’s changed and that’s really good. But it doesn’t feel any different to me and it doesn’t look much different”.

James came across the work of CeaseFire through his friend Alex Kotlowitz, whose article ‘Blocking the Transmission of Violence’ appeared in the New York Times Magazine in May 2008. They had wanted to work on a project together for many years, but unfortunately it was tragic events that made James and Kotlowitz decide to refocus on these communities.

“We’d both seen people who we’d come to know quite well who became victims of urban violence,” explains James. “In my case, two prominent people from Hoop Dreams, Arthur Agee’s father Bo and William Gates’ brother Curtis, both very prominent parts of that film and obviously hugely important in the lives of those families, have in the years since we’ve finished the film both been murdered. To see the impact of those losses on those families is something you don’t forget.

“It just felt like the right time maybe to do a film that tried to refocus public attention in some ways on this issue. It has felt in recent years like… there’s a collective feeling because murders are down nationwide we’ve solved the problem as good as we’re going to solve it, even though murders in most major American cities are still inexcusably high”.

Like the interrupters themselves, James’ camera is non-judgemental. Punctuated by the seasons, the film follows a year in the life of interrupters Bocanegra, Matthews and Williams without trying to impose a wider narrative, an analysis or a solution. James and Kotlowitz are content to remain observers, drawing attention to wider problems through illumination rather than preaching. The result is a film that wells with empathy yet never slips into sentimentality, and which provides an understanding of forgotten communities to which most of us would never gain access.

While James doesn’t see himself as an “issues” filmmaker, he does hope that some message will resonate beyond the film’s frame. Despite so much anger and violence, what emerge here are not stories of hopelessness but often of redemption.

“It’s incredible what individuals are capable of accomplishing on the ground,” says James. “These are communities worth saving. These are communities that can be saved, and to save them — to truly save them — it’s going to take commitment from other people than the interrupters”.

BY REBECCA HARKINS-CROSS