“We were settled. Everyone was good at what they did. You get to the point where you’re in the zone really. Before I was doing this band I had kinda weaned myself off music, there were points in my 20s were I was playing in like six bands and they wouldn’t even be your bands. You would just have a mate who would be like, ‘Oh do you want to come and play a gig?’ and you’d say, ‘Yeah sure yeah’ and you wouldn’t even ask if there was any money in it.”

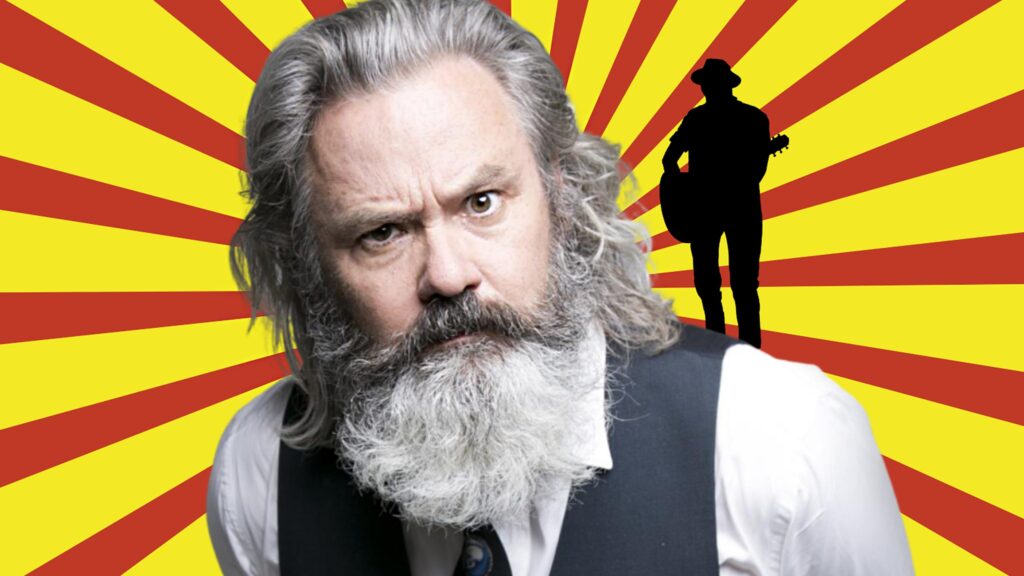

Nick Buxton, Dry Cleaning’s drummer, is explaining how the band had moved to a different stage in life before Dry Cleaning came about. They had settled down, you might say.

“I did this session gig once for Loose Meat, for the guy who recorded our first two EPs, Kristian (Robinson), I was playing in his band. And the guy who was playing keyboards, was a similar guy to me, and he was like, ‘Are we gonna get paid for this?’ And I was like, ‘What the fuck? You want money? You want money to do this, are you insane?’ And that was just the way you did it, you played with as many bands as you could.”

Lewis Maynard (bass): “By that feat though, we recorded our first EP.”

Nick: “Yeah that’s true, he recorded our first EP for like 200 quid.”

Lewis: “No the first one was free… oh no… the first one was 20 quid.”

Keep up with the latest music news, features, festivals, interviews and reviews here.

My chat with Dry Cleaning may have gotten off on the wrong foot, musing on how they have broken out as an indie darling at a more mature adulting age than is typical. I’ve already christened their full band Zoom appearance a democracy, an institution perhaps on the wane in the UK, but in this house, the speakers perform sentences by committee. My initial suggestion that they’re getting on in years (if not as much as myself) is taken on the chin as Nick retorts: “We’re pretty close. Closer than you might expect.”

Florence Shaw (vocals): “We look beautiful and young and youthful but we’re not.”

Lewis Maynard (bass): “And we feel fresh.”

Florence: “We’re feeling very fresh. But yeah we’re not. We’re mouldy.”

Unbeknownst to me, this fungal issue is likely relative to their having fully savoured the night airs of Cologne post-show the night before – hence their being propped up in a couple of hotel room beds and gifting the conference call a bare-minimum of eye contact.

Nick continues, “I don’t think any of us would have handled this situation well in our 20s. It is a lot of fun, it’s an amazing experience, but I think if this had happened to me when I was younger I would have really fucked it up”.

Tom Dowse (guitar): “We wouldn’t have been on this call for a start.”

Lewis: “We wouldn’t have woken up. We’re now responsible adults.”

Florence: “We’re very mature.”

Starting a band at such a ripe old age could mean that in place of youthful naïveté one could even be jaded, but Nick quickly jumps in, “Oh if we were jaded we wouldn’t be doing it”. I clarify that the musical knowledge and fully formed influences they’ve garnered grants a perspective where they might hear something new and instantly know the derivation, “Oh they’re ripping off blah”.

Nick takes my lead, “I know what you mean and I feel a bit of that and at the same time I feel like this is the richest creative period of my musical life. Obviously, I’ve got more time to put into it now. But also I feel very free and I think this band offers us a space to operate in that we didn’t necessarily have in other projects.”

Lewis continues, “I think we started with confidence as well, in ourselves and our process. There’s a lot of listening involved, we write via listening. I think that comes with maturity as well.” Florence grabs the baton: “We talk a lot about something being fun to play but not necessarily great to listen to. It’s really easy to be seduced if something is really fun to play but if you listen back and it’s kinda boring then we tend to discount those ideas. I would have done that less when I was younger, I would have been chasing something being fun. Which is fine, but I think we want to make something good.” Lewis is back for the final leg, “There’s songs where I would never choose to play like that, where I’m playing chords and stuff on bass. I would never be like ‘Hey guys I’m gonna do this!’” he laughs. “It sounds good so I’m gonna do it.”

This seems as good a time as any to throw a hoary music journo cliche into the pot, but I’ve an excuse for the aberration which I nervously attempt to detail while gesticulating wildly.

For all the glorious albums that have emerged to offer some small recompense from the COVID era, Dry Cleaning was one that made me sit up straight and say, “What’s all this then?” before keenly pondering unlikely relationships to artists like spoken word dabbling stoners Bongwater, council estate lo-fi Television Personalities, niche peculiarities Midget Handjob, rock poet Patti Smith and, now familiar with Florence Shaw’s inquisitive, contrasting and just damn effective collage lyricism, most pertinently, William S Burroughs’ tape collages on Break Through In Grey Room. Knowing the likelihood of disappointment – these are no conceptual art rock wankers – one still cannot resist asking if there’s an origin story. Not Peter Parker meets spider, but could there have been a conceptualisation of their sound or was it entirely organic?

Florence breaks the news gently, “The real answer is probably annoying. Right there when you were like, ‘Was it organic and boom there was Dry Cleaning?’, unfortunately that was true. It would be easier if there was more of a story, like we made a plan – but it was very casual. It was born out of what we each like to do and partly out of me being a beginner and wanting to do something accessible like talking.

“We had snippets of conversation, I was nervous to come to the rehearsal so Nick sent a few songs to me, like ‘You don’t have to just belt out a number, you can be a front person in whatever way you want’.” Reading elsewhere you’ll find these songs may have included Grace Jones, but I have granted an exemption from naming names. “(It was) just to remind me that I shouldn’t get in my head too much. But that was literally a text, it wasn’t, ‘Now let’s have a meeting’. It was one text and then I went ‘Oh yeah’. It was very organic, which sounds like such bullshit, but it was.”

Lewis shifts the focus to Grand Designs, “We’re influenced by our environment as well. In the first six months or so we were in a very small room. So I think all of us, that influenced how we played as well. We had to play to the room.” Buxton agrees, “We are influenced a lot by our environment. By the space, by the weather, by the political climate which you touched on at the start. A lot of the musical influences you read about a lot of the time aren’t really things we have mentioned. I think it’s a thing that all bands go through where you have to be digested by the media and then by the people that listen to your music.”

And spat out: “It’s true, it’s just how it works. It was frustrating for us at first but as you do more of this you learn to understand what’s actually going on and it’s just a way of people learning who you are and what you’re about. Over time you eat away at that and form your own thing but it’s not really possible to do that instantaneously. It takes time for you to establish what you are.”

Florence is still feeling guilty for trampling on my dreams, “The references you mentioned are nice to hear really because we get a lot of ‘Oh it’s like The Fall’ or whatever. I really like The Fall but I don’t see a massive parallel.” I forcibly interrupt her to agree, in that Mark E. Smith was frequently completely unintelligible, a foible Shaw does not suffer. With mirth, she proceeds, “Even something like Patti Smith is interesting because I don’t have any memory of anyone ever mentioning her before. Which I find really surprising. People always stick to the usual suspects. So it’s interesting, that’s a broader pond that you mentioned.”

While Poppies (Radio Ethiopia) is a fun counterpoint, it is a beat poet friend of Patti’s that fans of Dry Cleaning’s lyrical methodology should look up. Explaining how Burroughs spliced and manipulated tape recordings to achieve his own collage technique even piques the band’s interest. Aside from attributions to The Fall, journalists far and wide have been twisting themselves in knots to provide a moniker for their sound; while post-punk seems lazy, I profess some glee for one encompassing label – post-punk anti poet – particularly its possible glancing aside to NYC’s Sidewalk Cafe music scene.

While amused, Florence is having none of it. “I don’t get the anti”. The collage perhaps? “Yeah but I think that’s a legit way to write. All these terms, if you get stuck into them they drive you a bit mad.” It is entirely legitimate, Burroughs deemed his tape poetry collages an attempt to evolve his art form to keep up with modern visual art movements.

“Sometimes I think we should start calling ourselves pre-punk,” says Nick. “We have much more direct influences from bands like Sabbath or the movement in the mid-70s that came just before punk. Those very early rock and roll bands. I’m not going to start naming names and give a whole pile of false influences out but it’s a weird thing the post-punk, it gets used a lot.”

Listening now, replete in a PRAISE IOMMI hoodie, it’s not Sabbath that emerges; rather the expertly produced maelstrom of guitar, bass and drums with Florence floating singularly above the eye of the storm. In fact, I rather wish for a yarn with Tom about the interplay between Morrissey and Marr, but one might infer from reticence that his night in Cologne had extra sauce. Indeed, Tom draws the curtain for Nick, “This stuff only happens in interviews, we don’t ever talk about what we are – we just get on with it.”

Lewis provides more finality, “The post-punk (comparison) is so weak unless you view almost all guitar music post Sex Pistols as post-punk.” Indeed.

In light of the reflection on their balanced maelstrom, which reminds somewhat of Stephen Street’s work on Strangeways, Here We Come (The Smiths, 1987), with a minute to go I try to sneak in a discussion of their accomplished producer, and artist in his own right, John Parish. Perhaps there is not the legend attached, but his resume is not so distanced from someone like Steve Albini – they have even shared artists. For a debut LP, this seems as though it could have been intimidating.

“He really defuses that though,” says Florence. “I was nervous but I stopped after about 30 seconds. He doesn’t put it on you. I think he probably works hard to play it down. He probably knows that it’s not going to serve the record if you’re shaking in your boots and feeling really intimidated the whole time. He’s an imposing presence, but that’s his personality it’s not to do with his CV. Whatever job he was doing he would be like that. He is a very, what’s the word, singular sort of figure, almost more than anyone I’ve met, where he knows himself very well. And knows what he likes and what his intentions are with the record. He’s almost never unsure, and if he is unsure he says it out loud, nothing’s hidden. Everything’s on the surface – he’s never confused. That’s not to do with the CV, that’s just what he’s like.

“I found it really easy to forget about the things he’s done. Although I did read an interview with him very late one night when we were there, and it really freaked me out. And half the next day I was really nervous, cos it just reminds you ‘Oh this is scary’ but it only lasted a few hours and it was because I stupidly Googled him.”

Lewis enthuses, “A big part of why he is so good at his job is a big part of it is people management as well. Like on New Long Leg we literally met him and started recording within hours and we bashed out a song like every half a day. His people management and how he works and how he knows what to get out of you and how to get it out of you, he’s very good at that.”

Nick: “He’s very organised. He wants to work, ‘Lets work from 10am to 7pm every day and stop for lunch’. He doesn’t drive you through the night, because you hear about producers who want to get bands crazy, and push them to their limit and he will do that but in different ways, he will challenge you in ways that are very upfront, ‘What you’re doing there, I don’t like it – can you change it?’ That can be very difficult when you’re really keen on something, really set on a part you’ve written or you’re taking a brave step and trying out something new and he’s like, ‘Nah, that’s shit’ (laughs all round). That’s part of the process and you can either deal with it then or you can wait for the record to come out and have loads of other people say it. And then it’s in the world and everyone is telling you it’s shite.”

You can’t be a yes man…

“He’s not a yes man!”

In farewell and querying what audiences can expect, I am promised a bouillabaisse of material from the records and EPs, and Lewis has some interesting tourist discoveries awaiting, “I’m still confused by chicken salt – I heard that it’s green.”

Dry Cleaning are playing Meredith from December 9-11, then The Corner Hotel on December 12 and 13. Ticket info here.