Indie, pop four-piece The Kooks faced a similar lot of criticism – from the release of their 2006 debut Inside/Out, to the even more scrutinised third and recent, Junk of the Heart. Of course, by drawing a musical industry parallel between the Beatles and Kooks, I’m in no way elevating the latter to Beatlesque status. I’m simply commenting on the sometimes unexplainable logic of success and the evident fact that, in a large number of cases, records aren’t bought for their originality.

In reviewing the two-months-old (released in September this year) Junk of the Heart, NME Magazine referred to The Kooks as a “shrink-wrapped Libertines for pre-teens” and stated that Junk showed The Kooks to no longer be “kooky.” These kinds of accusations are as ubiquitous as they are contradictory. The word “kooky” itself implies a drift from the norm, which contrasted with a reference to being “just another generic British band,” or a PG, less heroin-induced version of The Libertines, just doesn’t seem to add up. It may be true that at times, a Kooks song could be mistaken for one of Maximo Park (especially with the second album Konk) or another indie British outfit, but then when they try to change, The Kooks get accused of no longer sounding like themselves.

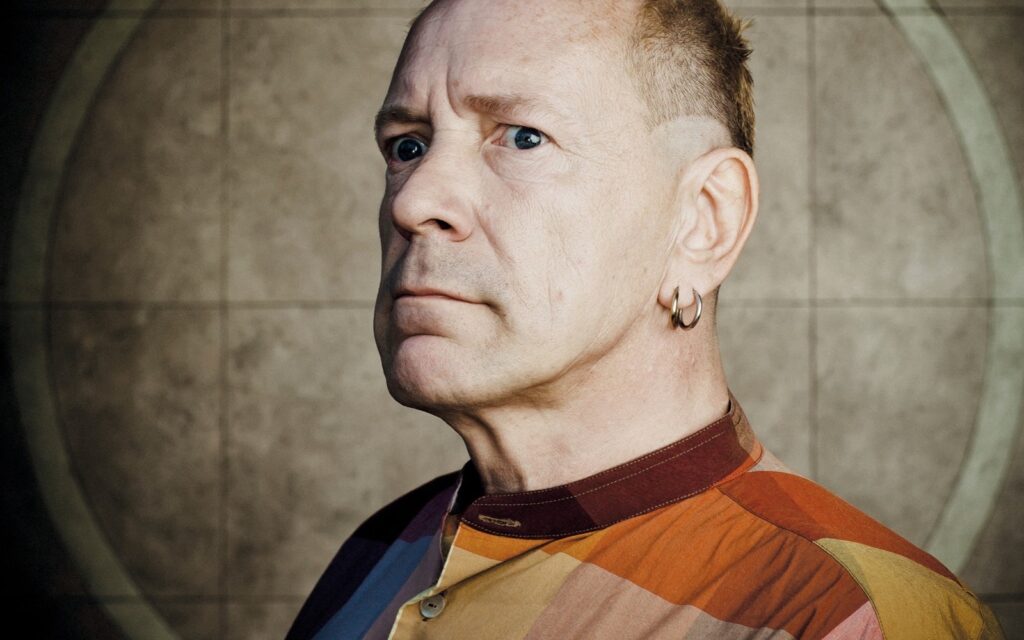

Guitarist Hugh Harris defends the new album and the seeming lack of kookiness attached to it.

“I think had we done another album that was like our first two, we would have given in to the way indie bands work these days, which is incredibly dull to me. It just seems like people hit a formula and that’s kind of it then – ‘We sounds like the Kings of Leon now, this is us. This is what we’re going to be doing.'”

“I feared for our band doing the same thing. Change is admirable I think. For our own sanity and health, we had to incorporate new things, reinvent the sound that we were interested in and that represented us – a sound that wasn’t miles away, but also that was quite an interesting twist.”

But in altering their sound, they weren’t trying to move away from sounding like other bands, but quite the opposite. It may have been the bunch of covers they did of modern musicians like MGMT, Foster the People and Gnarls Barkley which pushed them in the direction of a more computerised style of recording. Harris does note that he and Luke Pritchard (singer and songwriter) were inspired by these, but also that the evolution was slowly taking place before that.

“I think MGMT were a really interesting band when they came out. They did it really well. Not to say that we’re trying to imitate, just open our minds up more to modern ways of recording. Because you kind of run out of options if you just play rock’n’roll in a room and record it. We wanted to be upgraded as a band. We were so focussed on using quite vintage gear and being quite purist like that, I think through doing that we closed our minds to a lot of things.

The man he points to as being “there to open” their minds, is legendary producer Tony Hoffer, who also produced their first two albums.

“I think on the third album we allowed him in more. He really stepped up to leading us more in the direction that we weren’t sure of ourselves, just in the style of recording and bringing us into the new age. We’d always been fans of modern guys like Daft Punk and Air and all that lot but I think on this album, Tony helped us achieve a warm shimmer of computerised music and laptop music as well.

“We wanted to have modern sounds in the DNA of the songs so Luke and I, we started writing on laptops instead of our acoustic guitars and through that you write completely differently and using that as an instrument, you come up with completely different thing.”

The resulting mix came to songs like Runaway with a “disco dub step beat”, the skittering, synthesised drums of Is It Me (which has a chorus that could have been written by Supergrass) and the very Empire Of The Sun-like title song Junk Of The Heart (Happy).

Whether the band no longer sounds like The Kooks – something Harris laughs off (“to me it sounds like us, because we did it”) – or not, the unmistakable notes of underlying happiness which seems to come so naturally to the boys, considering they’ve kept it up for three albums, are still there. In fact, they had to scrap a lot of songs when they first started recording precisely because they weren’t as upbeat as The Kooks would have liked. And with this, they haven’t changed one bit.

“We were playing with a different drummer and different producer and it didn’t click right so, yeah the bounce isn’t there,” says Harris. But when they got Hoffer back, everything kicked into place. “You have to stay true to the sound that you discovered. If you found that, it’s important not to lose it. Upbeat, melodic, and uplifting melodies is a trait of ours, I guess.”