“[The Astor] is a destination venue,” he says. “This is a place run by film fans for film fans. It’s not like you’re just going down to watch a movie at the local multiplex. This is almost a museum in some respects. You come here and it’s taking you to a place that is touching on decades of cinema history. The audience aren’t just here to see a film, they’re here to see an event, they’re here to see a film presented with the curtains opening, with the little pre-show.”

After a few bumpy years – which saw relations between The Astor’s erstwhile tenant, George Florence, and the building’s owner, Ralph Taranto, grow increasingly hostile – in early April, the St Kilda landmark shut its doors. Consequently, fear set in that the iconic local picture house would soon go the way of the buffalo. Fortunately, the Palace Cinemas group promptly stepped in to take over Florence’s lease, and under Hepburn’s management, the theatre will reopen on Sunday June 7. Hepburn’s pleased to report that inside the Astor, not much has changed.

“We’re definitely keeping it as a single screen theatre,” he says. “I think that kind of picture palace aesthetic is integral to the location. We really wanted to give the building a slight bit of fresh air – a lit bit of paint here and there, a little bit of updating of the electrical areas, just some refinements. There’s no structural changes that are taking place. The projector equipment and seating has all remained.”

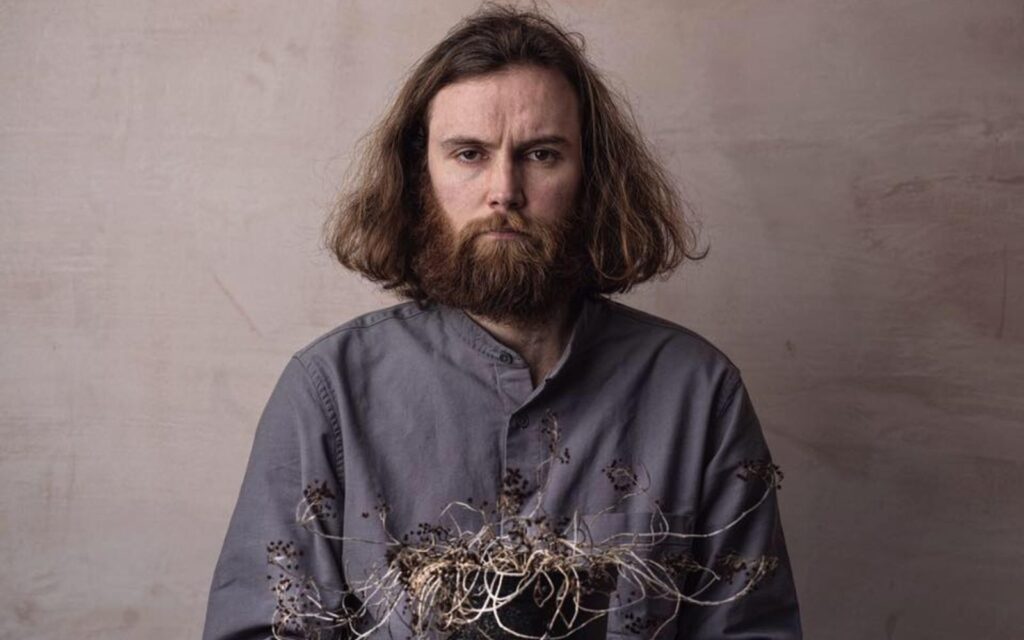

Some people would no doubt recognise Hepburn from his regular film reviews on ABC News Breakfast. Hence, you’re probably wondering whether this film critic is really the right person to take charge of the Astor Theatre. But Hepburn isn’t just an overly-eager movie nerd. In fact, he’s maintained a successful working relationship with Palace Cinemas since 2006.

“I started as a front of house worker at the Palace Westgarth,” he says. “Through that time I became really obsessed with the event cinema scene that was happening in the USA, so I developed a repertory program at the Westgarth of 35mm prints, usually of exploitation or other kinds of genre-cinema. I then went over to the Palace head office and started to assist with the national film program.”

A few years ago, Hepburn left his role at Palace in order to complete a masters in Moving Image Studies, and subsequently established himself as a freelance film critic. But, in spite of his respected literary and journalistic pursuits, it’s film programming that gives him the greatest kicks.

“I just really love being in a cinema environment and operating cinemas,” he says. “I think it’s a really unique job. You get to wear a lot of different hats and you get to show some cool movies. [So when] I got invited to come back to Palace and be involved with the Astor, it was such a unique opportunity that I couldn’t say no.”

A veritable film tragic, Hepburn’s fascination began at a young age and he’s since been done whatever it takes to make film his life’s chief focus. “It’s just one of those pre-ordained things,” he says. “I got taken to see Howard the Duck at Greater Union when I was two years old and it terrified me, but I was obsessed with going to movies ever since then. When it came to me doing professional stuff, the cinema just seemed to be the natural selection.”

A true indication of Hepburn’s obsession is that, despite being enmeshed in film for the entirety of his working life, he still wholeheartedly relishes the cinematic experience. “Going to the movies is like going to church,” he says. “It’s a real hallowed territory. You don’t have your phone, you don’t have any distractions from the outside world. When you go in through that door and the lights go down, you’re really entering another world. I think that’s one of the main powers of film. A great film takes you on a journey and that’s part and parcel of having your undivided attention to what’s going on. If you think about it film is actually a relatively young medium, in comparison to books or music, but it really has a way of inhabiting your psyche.”

It’s this sense of entering another world that’s made the Astor Theatre such a cherished cultural artefact, particularly since Florence took over the lease in the early 1980s. The theatre’s estimable reputation closely relates to a long-standing emphasis on classic films and cult favourites. The Astor has also distinguished itself by presenting repertory films in their original format – that is, on film. Thankfully, the Palace Cinemas takeover won’t interfere with the screening of such Astor staples as Poltergeist, Aliens, Baraka and Hamlet. Plus, in the lead-up to the re-launch, Hepburn’s secured some other rare 35mm prints.

“I’ve got a great 35mm print of the brilliant Ken Russell film The Devils with Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave,” he boasts. “I’ve also got a fantastic 35mm print of Mean Streets, the Martin Scorsese film. I’d say just shy of 50 per cent of the program is probably on celluloid. I’m also really excited about some of the other newer content that we have that is available in digital format. I’ve been able to get stuff like Big Trouble in Little China, Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise, Michael Mann’s Thief – stuff that doesn’t get screened very often.”

On the topic of rare screenings, the survival of the Astor Theatre will be celebrated with a red carpet gala event on Thursday June 25, which includes a premiere screening of director Gillian Armstrong’s new documentary, Women He’s Undressed, followed by a party in the building’s opulent foyer. “We really wanted to have people in, watch a film inside the single screen auditorium and then come out and have a chat about it,” Hepburn says. “There’ll be some food and drinks and live music. It’s just a really great way for patrons to re-establish their connection with the location.”

Armstrong, a Melbourne local, will appear at the gala to introduce the film, which takes a look at the career of the under-appreciated Australian costume designer Orry-Kelly. Kelly was a prominent Hollywood designer in the mid-20th century, dressing the likes of Marilyn Monroe, Bette Davis and Ingrid Bergman. In tribute to Orry-Kelly’s career, the Astor’s forthcoming film program will showcase plenty of his handiwork.

“[We’re showing films like] Maltese Falcon, Arsenic and Old Lace, Casablanca,” Hepburn says. “That’s one of the strands the program hinges off, along with it being an ode to classic Hollywood and classic picture palaces.”

The nature of Women He’s Undressed – that is, a new film that addresses classic cinema – aptly reflects the underlying ethos of the Astor Theatre. It’s not uncommon to feel as though looking backwards is a form of regression. Of course, if you’re too focused on the past, you’ll never get anywhere. But it’s important that we’re informed about our cultural history in order to frame our present thoughts and progress into the future.

“[Women He’s Undressed] is a really great statement on what we want to achieve here and the sort of films we want to celebrate,” Hepburn says. “It acknowledges some amazing works of cinema, but also is a new look on things. That’s a fantastic match to how we want to continue the operations of the theatre.”

BY AUGUSTUS WELBY