“It began to smoulder in my head really around 2008,” Kinevane reminisces. “Then it really took off after I had a trip to New York City. I was very depressed, and impressed in a strange way, at the amount of homeless people that were there. It made my first experience of New York City kind of hard, you know?

“When I came back to Dublin, Ireland was just coming out of a very wealthy period, but there was still an enormous amount of homeless people on the streets. I was very upset by that. I wanted to challenge that, question it. So that’s how it started, that was the genesis of it.”

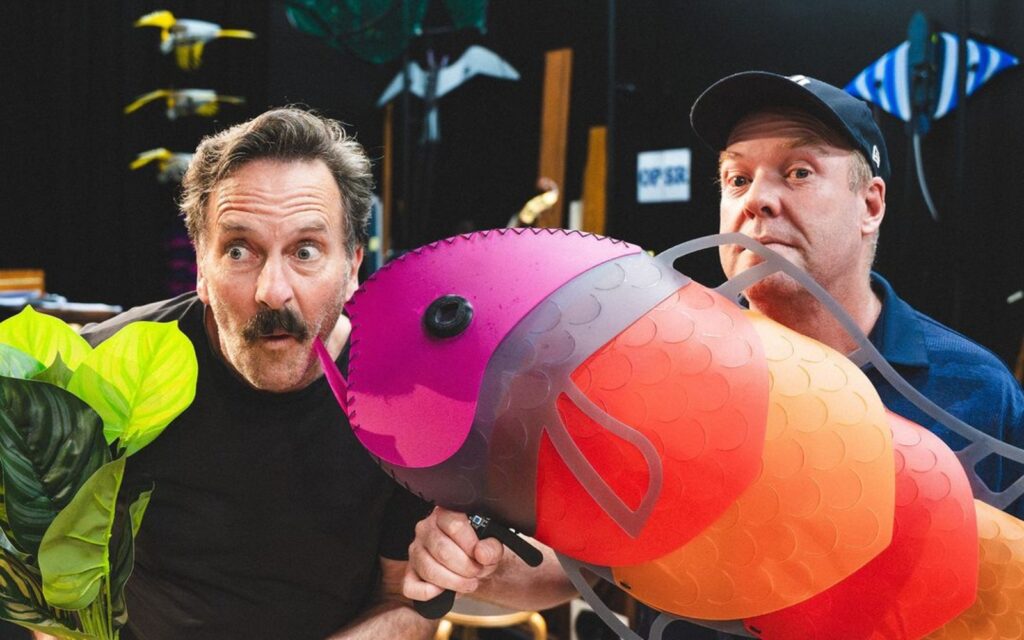

So what does an experience like that become when it finds its way into a theatrical production? “It’s a story about a man names Tino,” explains Kinevane. “His grandmother was a huge Rudolph Valentino fan. Valentino was of course a massive film star in the ‘20s, and died at the age of 31. He was probably one of the greatest film stars ever, right up to today. Tino has had everything in his life that we would consider normal. He’s had a teenage sweetheart, married her, had a kid, all the things that he thinks would make him happy. But through all this he feels dreadfully guilty and shameful about something which happened early in his life. His brother was a year older than him and took his own life after numerous attempts because of homophobic bullying in a small town in Ireland.”

Tino, tortured with guilt over not standing up for his brother and his sexuality, enters a spiral of depression and dispossession, ending up on the streets of Ireland. “The story really is Tino’s struggle to remain alive on the street. His mental health lets him down, it’s a torturous struggle for him.” Kinevane treats this tragic subject with a mix of hilarity and darkness. Through Tino’s eyes we see the everyday humour of life on the streets. We see how strange the so called “settled people” are to the disenfranchised, and how strangely we behave. “Tino observes us from below and takes the piss.”

This is the first time Silent has come to Australia, after a stellar season in Europe and America. “We’ve just come back from Los Angeles. Each region has its own particular sense of humour, its own particular sensibilities and eccentricities, but I’m really excited about going to Australia. The Australian sense of humour and my sense of humour are very similar and that there’s a huge appreciation of storytelling there. I’m very comforted because I don’t think there’ll be any problems of understanding or interpretations.”

A one-man show can be intensely personal, but Kinevane has not had any experience of homelessness other than interactions on the street. “The only experience I had was speaking to a lot of homeless people. I get down on my knees at eye level with people, talk to them and hear their stories. At the time I was thinking about the show house prices in Ireland were so ridiculously over the top it was almost impossible for people to buy a house. People were hurting. They were on a knife-edge. They could risk trying to own a home or pay an enormous amount of rent. It was a big mess really that whole period. I was interested in the fact that there were a lot of people and there are even now who are one or two salary cheques away from being homeless.”

Kinevane’s passion for social justice is what connects him to his subject matter. “I was very passionate about addressing the prejudices of people. Those of us that are lucky enough to have a house and those of us that are lucky enough to rent an apartment – we can be quite flippant at times, we don’t actually count our blessings when it comes to possession. I wanted to challenge my thinking too. Why do I walk past a homeless person and not look at them sometimes? What can I do to help maintain their dignity? I suppose I also have a latent sort of anger in me about the mental health system in Ireland. We seem to be highly developed when it comes to deal with matters of the physical body but the penny hasn’t dropped that it’s perhaps even more vital to look at the medicine of the mind. We need to make sure that people feel safe and they feel nurtured and they feel that if their mind is broken, even temporarily, that there’s hope, that it can be fixed.”

BY JOSH FERGEUS