“The writing on this record was an inward process as opposed to a reaching out and absorption process. It was more things that had built up in his conscience and the songwriting was an outlet for that, so that he would be the same person in his songs as he was off-stage… the idea of getting true to oneself.”

This philosophical mindset clearly rubbed off on Pecknold’s band mates. “In my life, I’m also coming from a different place than Robin, experientially,” he muses. “I grew up in and consequently grew out of Christianity, but the idea of self-improvement and wanting to aspire or transcend to something else is something that has been a big motivator for me in my life… would it be through guilt or fear or desire for thrills or changing or new experiences or understanding.

“And I think [it’s] a motivator for a good amount of people… the interesting part is ‘what’s the explanation for that motivation?’ For me, that’s an area of interest – to know why I want to go in a certain direction,” says Wescott, “because sometimes I don’t really have a direct channel to my sub-conscious like I wish I did. Robin had an upbringing that was free of religious suggestion, but I think the idea of wanting to meet your aspirations is a very universal concept for people.

“We didn’t have an album title even when we were mixing the album,” Wescott relates. “Helplessness Blues felt a bit like a thesis statement or word association that reflected some of the concepts, sentiments and ideas that Robin was addressing lyrically.”

There’s always been a rare depth to Fleet Foxes’ music – the seeds of which were sown when Pecknold and Skyler Skjelset (lead guitar, mandolin) became close friends at Lake Washington High School, and began making music together after bonding over a mutual love of Bob Dylan and Neil Young. It wasn’t long after they changed band names from Pineapple (seriously?) to Fleet Foxes that Seattle producer Phil Ek was so impressed that he helped the band record their first demo, the self-released Fleet Foxes EP, in 2006 – stating that Pecknold “had talent coming out of his ass”. By late 2007, their Myspace page had racked up a quarter of a million plays in just two months. Despite having not released anything yet, the band’s demos had created massive word-of-mouth exposure and resulted in their signing with Sub Pop Records.

There’s no denying Fleet Foxes’ incredible influence on alternative music in the past few years. They not only drew millions of listeners into the realm of harmony-drenched folk, but turned it into both a successful and desirable pursuit. Just like their inspirations – Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young – Fleet Foxes combine beautiful harmonies, evocative lyricism and sublime musicianship. The quality of their songwriting sets them apart from most of their peers and remains inspiring to emerging songwriters worldwide.

Released in June of 2008, Fleet Foxes’ self-titled debut album received almost instant status as “a classic” and was named album of the year by MOJO, Pitchfork Media and The Times. On the UK Album Chart, it debuted at number 11, peaked at number three and became the first gold certificate record released by Bella Union. Everything about the album was mesmerising including its cover art (the 1559 painting Netherlandish Proverbs by Pieter Bruegel the Elder) and Pecknold’s note on the album sleeve, which included the memorable lines: “I guess I was just a private kid and music was a private experience for me. I can even remember the certain kind of darkness my room would have when I was in there alone listening to records. I can listen to music and instantly be anywhere that song is trying to take me. Music activates a certain mental freedom in a way that nothing else can, and that is so empowering. You can call it escapism if you like, but I see it as connecting to a deeper human feeling than found in the day-to-day world.”

Pecknold and his troupe would begin recording demos for Helplessness Blues at Seattle’s Hall of Justice studio in October of 2009. “It started out really open-ended because we had been touring for about 18 months after the first record, so we took a little bit of time off and Robin started writing,” Wescott explains. “We reconvened maybe a few months later and I remember there was one meeting where we knew that we couldn’t impose anything on this process and we just kinda had to take it as it came, so we didn’t really have any guiding principles or rules going into it. The process and what became the album was a result of discovery and appreciation of those discoveries for each of these songs.”

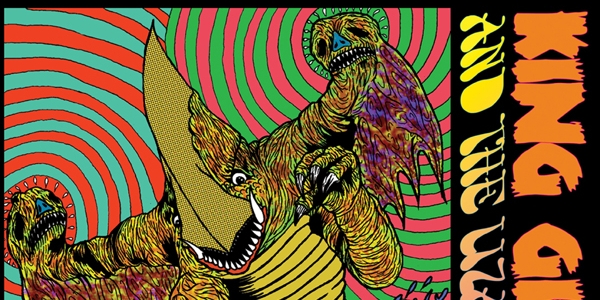

Released in May of 2011, Fleet Foxes’ sophomore album was also met with universal acclaim (Popmatters named it album of the year) and received a Grammy nomination for Best Folk Album. Incorporating a lot more traditional instrumentation, Helplessness Blues features a country lilt, is less pop-oriented, slightly darker and palpably more introspective/analytical/personal. It also features enthralling cover art – this time, illustrated by Toby Liebowitz and painted by Christopher Alderson.

The dreamy closing track, Grown Ocean, was written by Pecknold during his support tour with Joanna Newsom last year. “Over the course of nine months, he’d be continually re-introducing the material, tweaking lyrics and different things,” says Wescott, “and as a band, you adapt to the new songs and come up with ideas for them that thrill you and can consistently do that. After he came back from Joanna Newsom, we really put our heads down for a good while longer. We do spend a significant amount of time making a record because you have to give yourself the time and space to let things happen, and that’s how the first record happened.”

After the Joanna Newsom tour, the band recorded at Dreamland Recording Studios before moving in and out of numerous studios during the second half of last year – a period comprising bouts of illness, the usual feelings of creative doubt and plenty of rewriting. In what would become an immensely rewarding experiment, Helplessness Blues saw Fleet Foxes exploring an abundance of traditional instrumentation including the hammered dulcimer, tympani, tamboura, marxophone and Tibetan singing bowls.

“I went to this store and this guy had all these copper bowls that he had gotten from Nepal,” Wescott relates with palpable glee. “It’s quite interesting – I think the copper comes from India, but then is shipped over to people with entirely different belief sets and interests, and they actually fashion the bowls. There are hundreds of them and they’re not tuned to any particular note in the equal tempered scale, so I just went through the hundreds of bowls to see which ones were the most in tune with the song that I wanted to use them on and then I got them. I used these huge, heavy copper bowls for the end of The Shrine/An Argument for these longer drones. I rubbed the perimeter of the bowl with a cloth-covered dowel, which creates these really clear resonances.

“And then I also had a tremoloa, which is a Hawaiian stringed instrument that I really enjoy,” Wescott enthuses. “It has this lovely sound that gives melodies a strange, dark enveloping quality. I was trying to use instruments like programmable music boxes and zithers, just so that I could have smaller sounds that would accentuate what Robin was singing with just him and his guitar, and I wanted to have a relative perspective of smaller instruments in relation to his voice and the acoustic guitar. I brainstormed a lot in trying to find the right instruments for the right melodies and for certain properties of the melody.”

Since mesmerising music lovers with their self-titled debut album in 2008, Fleet Foxes have continued to stir and inspire while exuding an elusive, mystical air. There’s something intrinsically magical within those multi-layered harmonies and the manner in which their melodies transcend time, environment and style. As is the case with artistic genius, one cannot pinpoint the reasons for such brilliance, but rely on the omnipresence of its roots, which – in Fleet Foxes’ case – lie in a pure and spiritual abode; one in which sincerity and fluidity of emotion is as intrinsic to the music as the shimmering textures of its meticulously-arranged melodies. Pecknold stated that “the most enjoyable thing in the world is to sing harmony with people”, and Wescott happily agrees.

“Singing is this really amazing thing because it’s so related to your identity and your physiology, so to sing and first of all be breathing and using your body to produce a sound is a really satisfying thing,” Wescott conveys. “And to do it collaboratively… when it’s good, it’s good. But when it’s bad, it’s bad,” he laughs. “Singing harmonies is very satisfying because it’s four people coming together with their own instruments, which is themselves and their identity coming together and making a composite sound of all those things, so it’s really satisfying even on a personal, non-physiological, emotional level.”