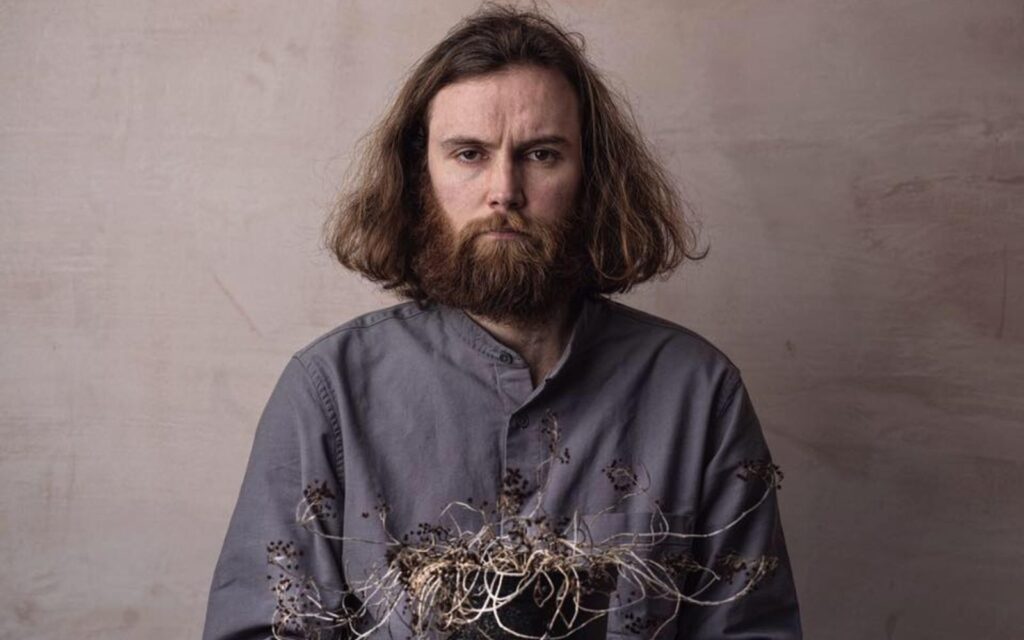

Hayden Spencer plays Kjell Bjarne, oversexed, understimulated and Elling’s unlikely partner in crime. “They’re given a kiss and a prayer and sent off into the wind, if you like,” he laughs. “And you see how they persevere. My character is not without his obstacles in society – he has a really high sex drive and a low social moray, and everything he’s going through he’s probably dealing with for the first time.”

In a piece directed by MTC favourite Pamela Rabe, Spencer says they’ve tried to stray away from specificity in dealing with the characters’ illnesses. They exist, as many characters do, as flawed human beings in an unfamiliar environment. “The more that you start to identify and lock down the precise condition the more it’s possible that it could be dismissed. So it’s important to artistically keep things relatively broad in that respect. But you’re doing that from a mathematical point of view – we’ve been quite specific in being general.”

Though Kjell Bjarne does have his share of odd quirks. “It will become apparent to the audience some of his limitations – principally with the single-minded focus on sex and taking that out into the general populous.”

As a 2001 film, Elling did particularly well, receiving nominations for swag of awards and appearing at The Toronto Film Festival, but Spencer deliberately hasn’t seen it. “I haven’t checked out the film, but I’ve started reading the book. Not only have I been involved in the rehearsal time but also out of hours, so I can piece together this puzzle. I guess the film would probably be distracting, because my imagination is still at work when I’m reading the book, and I can still sort of place myself in the role, but if you see someone portraying the character that could be misleading.”

What’s common about all of its adaptions is it doesn’t shy away from the subject matter’s potential darkness, but gives its characters appropriate comic relief. It’s been called “sweet”, “sarcastic”, but underlying the humour is a conversation about society’s fringes. “As we’re all well aware mental illness is a lot more prevalent in our society than we’d probably care to admit. And that’s obviously been the focus of a lot of groups in recent years, certainly,” says Spencer.

“These two characters are probably the two least likely candidates from whom we can extract information or a moral viewpoint from, if you will. But in saying that, in the passage of the play both characters initially are really quite confronting. The audience may very well question whether they want to spend an evening with these characters.”

But Elling makes sure you do spend the evening, the narrative offering a redemptive perspective on their illnesses. “It’s a journey of [the audience] hopefully falling in love with these guys and seeing life through their perspective, through their eyes. They struggle to answer a telephone – the basis of a whole scene is how to answer the telephone – whereas most of us in society have never had issues with that.”

One of the most humanising elements, reflects Spencer, is the friendship the pair form. They may be misunderstood oddballs but at least they have each other – a romantic notion which sees the characters develop and change. “Neither of them have had a history of friends or friendship,” he says. “It becomes apparent that they’re useful to each other, very useful, to the point where the exterior force of the powers that be have decided that they will work well together in an apartment in Oslo.”

He became particularly attached to the character he played for the childlike wonder adults soon forget. It reminds him of when he had his own children, he says. “They have to learn to trust each other, they have to learn to love, they have to express their feelings and have control over their feelings. So everything they’re experiencing they’re experiencing for the first time which is really beautiful – like when my son and daughter were born and you’re seeing life through their eyes for the first time. It’s a really beautiful thing, so that’s what I really see in these guys – they’re dealing with a dilemma too. They’re having all sorts of feelings for the first time.”

Ultimately, Spencer thinks the play has a task in altering perceptions about mental illness – one that it willingly achieves. “I hope that one of the things this piece is saying about mental illness is requesting the audience to look beyond their limitations, and trying to have a closer association to their internal drivers which invariably will replicate their own.”

BY BELLA ARNOTT-HOARE