Most famously reflected in the philosophy and design of the Bauhaus school, the modernists recalibrated the balance between form and function; in the post-World War II world, modernism, helped out with the growth in the plastics industry, spawned a new era in industrial and consumer design. Everything from chairs to lounge suites to light shades to houses was infused with the modernist style.

A few years ago filmmaker Jason Cohn began noticing the proliferation of modernist furniture in retro stores in his hometown of San Francisco. Despite not having a design background, Cohn took the re-discovery of modernist style as the inspiration for a documentary on the designers who came to dominate the design and architectural market after the Second World War. Part way into his project, Cohn realised that the story of two protagonists of the modernist school – husband and wife team Charles and Ray Eames – would itself make for compelling documentary cinema.

“After I started reading about the designers of that period, and what they stood for – they had a profound philosophy at work. And then I started reading more about Charles and Ray, and I realised that their relationship was itself a wonderful story,” Cohn says.

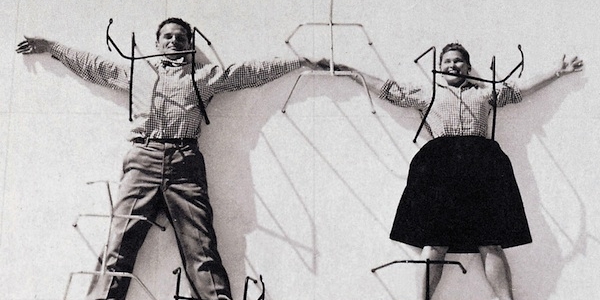

Eames: The Architect and the Painter tells the story of Charles and Ray Eames, and the couple’s impact on American design. Charles Eames was a struggling architect in the years preceding World War II. Already married, Eames met and fell in love with Ray Kaiser, an aspiring young painter. Charles and Ray eventually married and began a design practice together. An initial attempt at what later became the famous Eames chair failed, before the Eames used the United States Navy’s demand for splints to refine the design process.

Charles and Ray went on to found an eponymous design business that would continue until Charles’ death in 1978. Along the way, Charles Eames particularly became a feted figure in the design and architectural world; Ray’s contribution would also be celebrated, though without the adulation offered to her more publically prominent husband. While the Eames style is well known, Cohn says the more significant aspect of the Eames’ contribution to design was the process by which identified problems became design solutions.

“People who know Eames more deeply realise that they didn’t have a style as such – each design was specific,” Cohn says. “What I think really endures with Eames is the process of approach to design problems, the relationship between the designer and their client, the approach to yourself and your broader public perception. More broadly, Eames represented a seamless relationship between work, play and love life,” he says.

While it was Charles who tended to be front and centre in the Eames publicity machine, Ray’sinfluence on the Eames design philosophy and style – including the now legendary corporate promotional films Charles and Eames put together for clients such as IBM – has been subject of critical, and positive review in recent years. “You still hear people talking about ‘Charles Eames design’, but things have come a long way,” Cohn says. “A lot of feminist scholars have raised awareness of Ray’s contribution. And there’s now a bigger recognition that just because she wasn’t in the public eye doesn’t mean that she didn’t play a big part in running the company.”

What does remain a matter of contention is the part played by other designers employed in the Eames’ design business. Eames: The Architect and the Painter touches on such matters, though the various employees interviewed are all apparently devoid of ill-feeling toward their former patron and employer. “There is one person who’s taken a stronger line,” Cohn says. “Marilyn Newhart didn’t work there as such, but she had worked with Charles, and her husband John worked there, and was a key staff member. Marilyn has a very negative and bitter perspective on that question, and believes that Charles was very hands off, and her books have had a real influence on the historiography of Eames, though not everyone agrees with the research she’s undertaken,” Cohn says.

Eames: The Architect and the Painter captures Charles Eames’ very charismatic public reputation; despite its focus on the romantic and symbiotic relationship between Charles and Ray, the film notes Charles’ marital transgressions, including his affair with Eames staff member Judith Wessler. Cohn says finding the right balance between the Eames art and relationship, and Charles’ human failings was difficult. “As we were making the film what started to emerge was a love story between two artists, who worked together and built a business,” Cohn says. “So the fact that he wasn’t faithful to Ray, well it would have been dishonest not to mention that. And when we spoke to Judith Wessler, and her account of the affair was so touching, we felt we had to include that in the film.”

By the time of his death, Eames was a towering figure in the design world, although Cohn doesn’t believe Eames ever lost his original humility. “I think he did have a bit of an ego, but I don’t think he got carried away,” Cohn says. “It wasn’t like he was being treated like a movie star – it was only in the world of architecture and design where he was feted. What mattered more to Charles was what his friends thought of him, especially the scientists, engineers and physicists that were around him.”

BY PATRICK EMERY