“I haven’t had a day job in years,” says Bondy. Even before Verbena had any real success, this was still the case. “Some people would argue that in order to get anywhere in the first place as an artist or a painter, or whatever it might be, the work doesn’t really allow for ‘part-time’ commitment,” he says. “I remember seeing an interview with Denis Johnston a while back where he was talking about getting started, struggling as it might be, and he said that you need to not have a job. The interviewers then asked him, ‘How do you do that?’ He replied simply: ‘Well, the first part of not having a job is not having a job…'”

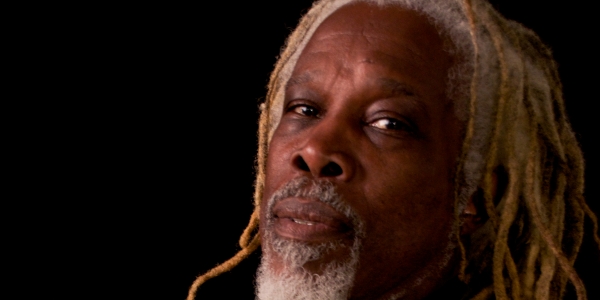

For Bondy himself, finding the path to success was not an easy one, with the songwriter relying heavily on the support of friends and family when first starting out. Often housesitting, dog-minding or hitting up family and friends for places with cheap rent, Bondy had no real choice but to dedicate himself fully to his art, because as he says, “I don’t work very well in the straight world.” It’s a self-professed fact that he likes to make a spectacle of.

For instance, while most press releases sent to me come laden with a series of italicised quotes from various media outlets, lauding whatever album for its genius while at the same time pushing the limits of hyperbole, with Believers, these quotes were instead filled out by normal, everyday people who happened to make Bondy’s acquaintance over a time of hardship creative development.

“The tall thin guy?” asks Ray Anne Murphy, attendant at the Spring Market Bondy visited. “Oh yeah, he came in here every morning for three weeks, bought the same thing every day (one tube of Krazy glue and a sausage biscuit). I couldn’t tell you what he did for money.” Or Gladys Broussard, secretary at B&O Railroad, who also recalls a unique insight into the songwriter’s character. “Not many people know this, but he’s not a bad horn player. But he only played during particular celestial events. At least that’s what he told me.” Some may see this as pointlessly silly or detracting from the seriousness of the music, or Bondy himself, but thank god it does. Believers, being such a well-crafted and polished collection of songs, and having such a sense of brooding seriousness to it, could use something silly to lighten the mood.

But looking at the album more objectively, the music itself shows Bondy as an artist at the height of his powers, a songwriter who through years of playing has refined his style and craft to a keen edge. A rich offering of dusty Americana, with tiny slices of external influences inserted into the songs like blocks of butter slid beneath the skin of a roasting chicken, his music clearly pays tribute to the great American songwriters yet isn’t afraid to put a toe or two out of bounds. Album opener The Heart Is Willing sees Bondy touching on krautrock with its motorik rhythmic bent. The Twist takes the album’s austere alt-folk character into vintage slowcore. There are more examples, but in each and every case what shines through is the effort and dedication behind the glueing together of these disparate styles.

Heaped with acclaim from reviewers all across the media, all speaking of his flawless appropriation of Americana with great reverence, Believers is quite clearly the product of hard work, of struggle and perseverance. Now in a position where the hardest times, the penniless and sleepless years, are behind him, he can now live, if humbly, from the proceeds of his music. And yet, as we all know, ‘the struggle’ only subsides for so long. Challenged in a new way, Bondy now enters a second realm of hardship – one of ‘success’ and ruled by the marathon of achieving longevity and the process of remaining inspired.

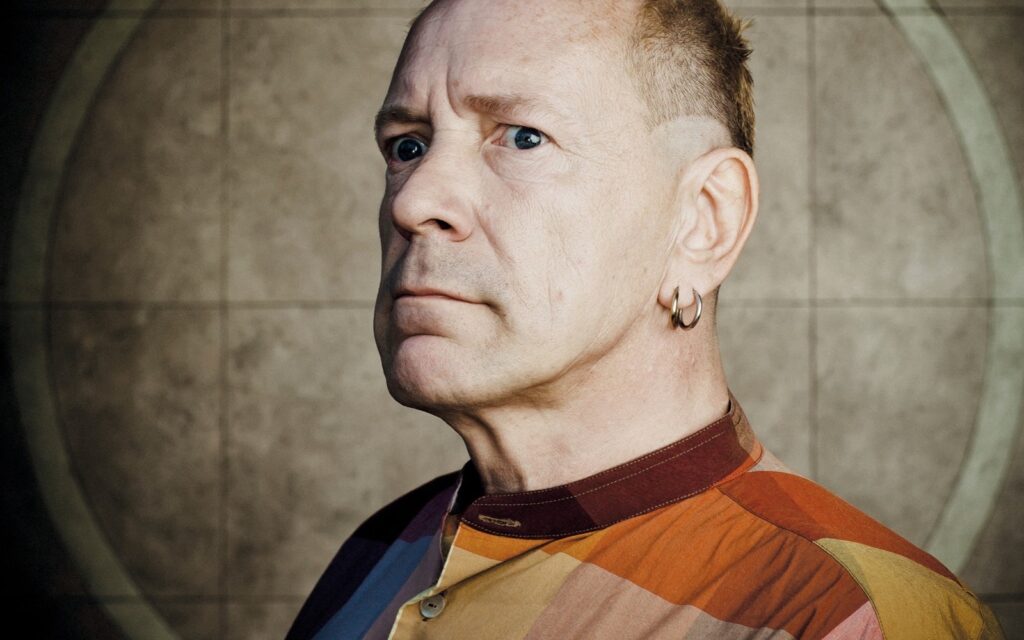

“Somedays grass is grass, and somedays it’s more than grass,” he says of inspiration. “It’s important to keep yourself open, but in the midst of all this travel it’s hard,” he says. “The tendency is to numb out because it’s kind of painful to keep yourself open. I don’t know many people who do it successfully over long periods of time.”

Sounding very much like the old hand he is painted as, understandably so – after over eight years in the industry – there is still plenty of romanticism left in him about why he chose this musician’s life and what keeps him making music. “When I’m in the middle of millions of acres of corn in America, in the wintertime, I always end up asking myself, ‘Why am I doing this?'” he tells us. “But every once in a while things sort of light up in a different way and that’s why you do it, I guess…I haven’t seen it all. I haven’t heard it all. I haven’t even mastered anything. In fact, I don’t think you can. But there is still joy in it for me. There’s still joy in the art and in the act.”