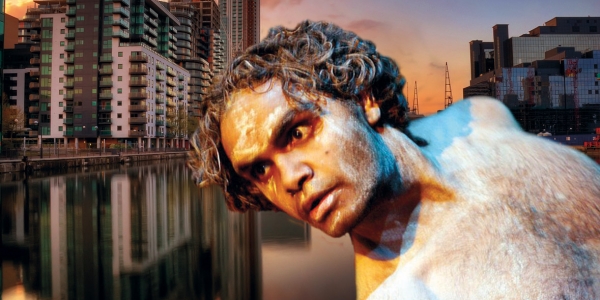

The show tells the story of Jim, a smart, young, indigenous man who has graduated from law school. “He gets hired by a very prestigious large law firm in Brisbane,” explains writer and director Stephen Helper. “The story follows him as he tries to climb the corporate ladder in the firm and balance his ambitions with his heritage, his culture, his family and the questions about identity, about who he really is.”

Helper worked collaboratively on the musical with songwriter Marcus Corowa and actor Leeroy Bilney, whom he cites as its inspiration.

“He [Bilney] had this image in his head of an Aboriginal businessman in a suit and a tie, looking very corporate, but then opening up his jacket and his shirt and taking out of his briefcase ochre or paint that would be associated with his culture, as if to remind himself of who he really is. And then he does up his shirt and goes off to continue on his way. I was really captivated with that.”

Another source of inspiration for The New Black was Helper’s work on a show in Brisbane called Soul Music, devised in collaboration with students at the Aboriginal Centre for Performing Arts. The students shared their experiences of what their lives are like now, and how they do – or don’t – feel connected to their past. Then they talked about songs that might help express these feelings. Much of this was the titular soul music, including songs by Marvin Gaye and Aretha Franklin. That’s where Helper met Corowa and Bilney.

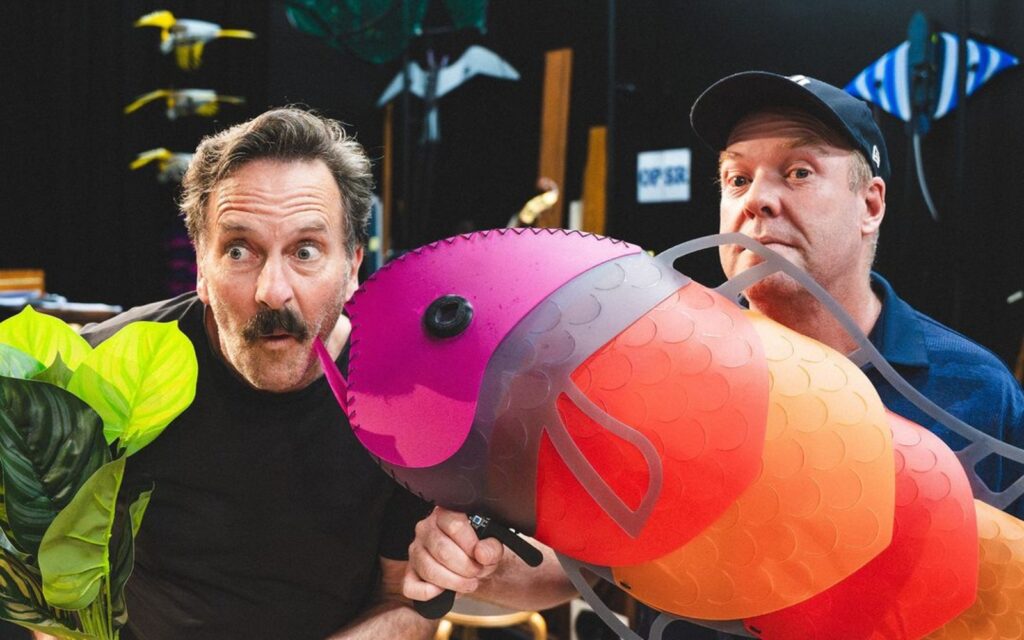

“I said to Marcus, I said to Leeroy, ‘I think we’ve got a musical here’,” he explains. “I don’t think they really believed that much would ever happen.” They worked on a new show with original music by Corowa and book by Helper, then presented a 20-minute piece in Sydney late last year. The Melbourne version has been extended to 40 minutes, followed by a 15-minute Q&A session.

The New Black features many different styles of music, including soul, ballads, rap, a tap number and traditional musical theatre songs. Indigenous musical elements like clapping sticks and didgeridoo are mainly used as “flavouring”, Helper says. “It’s very, shall we say, postmodern in the way we’re approaching this, because we want it to reflect our culture now, which contains so many different things that we can draw on. And it’s fun!”

“We’re not just doing it because we really want to have a tap dance,” he adds. “We’re working on the story and then, ‘How do we get this across? What would be fun? What would be satirical to really drive a point home, but yet you’re still laughing? Where’s the real emotional moments, where we really need to settle down and be more serious?’ And the musical ideas have come from that. We didn’t necessarily set out to write a show with a lot of different styles of music, it just evolved that way.”

Helper emphasises the way the show uses humour to tackle more sober questions. “It is a musical comedy. It does deal with very serious issues,” he adds. “There’s a sort of Eddie Perfect nature to the show in the sense that it’s satirical but it has a point to make and you’re laughing but thinking at the same time.”

“We don’t take ourselves too seriously. Well, we’re trying not to anyway. But at the same time it’s very truthful and ultimately uplifting.”

One might expect that writing about another cultural group for the stage would pose challenges like accurately representing their voice. Not so, according to Helper. “The challenge is not so much in the writing as in getting your head around what it is we’re actually contending with. What is it that they actually have to deal with every day?”

Helper visited an indigenous community on the far west coast of South Australia as part of the process of developing the show. “It was really eye-opening,” he says. “I visited Leeroy Bilney’s family.”

“And it was great because they took me out to the bush, they told me stories of the area, they cooked me kangaroo tail on the fire they made in the bush. And it’s all the real deal. It was beautiful.”

In his North American drawl, Helper says that the experience gave him confidence in portraying indigenous people on stage. He explains the two effects it had on the show: “One is a kind of confidence about talking about what we talk about; that we’re not making it up, that the issues and the racism and the political questions and the social dynamics and all of this stuff that we’re writing about – in a very entertaining way, I have to emphasise – gives us a sort of a confidence. And we secured permission from elders to talk about certain things.”

“And then there’s the spiritual dimension, which was already in the show, but it gives it a greater depth of authenticity.”