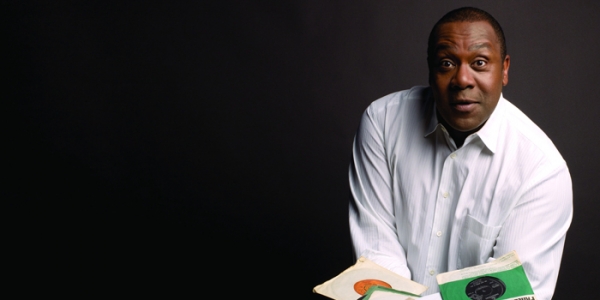

Lead actor Ash Flanders has his work cut out for him to perform as part of the ensemble show. His roles in the production switch between a young girl, a waitress, a male Asian chef, an old man and an insect. While this sort of feat requires suspension of disbelief on the part of the audience, it also requires deft characterisation and a honed malleability on the actor’s part. Which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, he says. “That’s what I love as a performer. It’s what gets me off,” he purrs with ironic sexual overtones.

Though the setting could be in any international metropolis, the play is quite specific. Written by playwright Roland Schimmelpfennig, it explicitly examines the experience of immigrants into Germany with a dry, laboured Germanic sense of language and a bizarre interest in brutality. The translation of the text, says Flanders, is interesting because of its typical German formality, but the microcosm it examines is undeniably human. “In terms of Australian audiences I think it will be easy to relate to. It’s that universal problem of: who are your people? Who do you look out for? Who should you look out for?”

Ultimately its focus is the experience of displaced people, immigrants, and the connections and interrelations between people. This, thinks Flanders, transcends specificity and comes pretty close to the plots of soapies. “Someone’s leaving, or having an affair, or having a baby, someone’s dying. The stories are almost hackneyed in that they’re so familiar, it’s something we’ve seen on Summer Bay, but it’s through this weird lens of a German slash Asian world.”

The story’s initial action is centered around the haphazard removal of a tooth. “The [character] can’t go to a dentist, he doesn’t have any papers, so they have to do an extraction in the kitchen. So it’s got that German love of violent imagery, a savage world. It’s kind of bleak and poetic.” And it highlights issues of Illegal immigration and how people smuggling has become common in Germany.

Where the immigrants are often demonised, Flanders says the most startling thing about the trend for illegal German immigration is consistent exploitation. “I’ve been reading people get brought over to be chefs in Germany in Asian restaurants, but you get over there and you’re getting paid so little and the loan – they just make up what number that is. So people are sleeping in restaurants, sleeping in laundries, and their family back home is being threatened if they try and leave. So it’s a seriously well-oiled machine and there’s something of that in this play.”

In a climate of a ‘stop the boats’ campaign cries, a persistent fear of invasion from the ‘Other’, the play for Australian audiences could encourage empathy. “That could be you, it could be anyone, it could be other races coming to Australia, or displaced indigenous people. It’s allegory.

“The people working in this kitchen don’t have the luxury of wishing life could be different. And yet all the other characters say at one point that they wish they could be someone else but their lives are infinitely easier than the people who are working in horrible conditions.”

The story is underpinned by a classic parable. The cricket character Flanders plays references Aesop’s fable The Ant and the Grasshopper, an ambivalent moral lesson about hard work. A grasshopper, so it goes, spent the warm months singing while the ant worked to store up food for winter. “The cricket didn’t work enough during the summertime and when winter came they weren’t able to survive, which ties back into capitalism, this idea of a hard work ethic for the benefit of the group. But that’s another thing about the play, because you could get it to say a lot of things,” says Flanders.

The play is not necessarily moralistic though, and Flanders notices there are moments of dark humour spread throughout – it could even be seen as slapstick in persuasion amidst the chaos of actors switching roles, changing settings and general misunderstanding. “It’s kind of madness, the way humans fail each other is always funny. The way language fails us. People can be really horrible to each other and I’d say it’s darkly funny. Even the tooth extraction is funny, and magical and weird.”

And although it may be a stretch, Flanders hopes that theatregoers will get a kick out of using their imagination to bring the piece to life. “[Theatre] is place where, if I say that I’m wearing a red dress and I’m gorgeous you believe that, because we’re here to make believe, and have fun. Which has always been a big part of why I make theatre.”

BY BELLA ARNOTT-HOARE