A look at a longstanding issue that’s only recently being remedied.

Leaving Allen Street is a Melbourne story. Created by Katrina Channells and Bridget O’Shea of local production house We Are Yarn, the feature-length documentary follows 30 adults living with intellectual disabilities as they move out of an institution and into public housing.

The film centres on the Oakleigh Centre in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs. The significance of the move cannot be understated, with many of the featured individuals having lived in the institution throughout their adult lives.

The institution had provided high levels of support, but it also precluded any meaningful connection with the outside world. Leaving Allen Street reveals how many of our basic freedoms – such as going to the shop or walking through the park – are denied to people in institutions like the Oakleigh Centre.

“At the start of the journey of making the film I was really unaware of the systemic institutionalisation that’s a part of our history in Melbourne and across Australia,” says Channells, who directed the project.

“It was a bit of a shock and that was part of it, going, ‘Wow these people don’t even have a choice to go down and get litre of milk’. They weren’t allowed to go to the shop at all actually – people did shopping for them.”

Shopping wasn’t the only off-limits activity. The Oakleigh Centre residents were confined to a locked facility and forced to adhere to scheduled meal times. They couldn’t even go to the shower or the bathroom unless a staff member was there to supervise. They also had shared bedrooms and facilities.

Leaving Allen Street observes the planning and implementation of the Oakleigh Centre’s Community Housing Program, which was designed to “provide individuals with opportunities to develop independent living skills, access community activities and experience a lifestyle that is the same as other community members”.

We Are Yarn were initially commissioned to shoot a few promo videos for the centre, but they ended up filming for four years.

“Once we met all the residents and the families, so many stories popped up,” says Channells. “Every time we went to film one story, like ten or 20 stories would pop out. So we had to follow them. It was just such a big story to tell so we thought we had to do it.”

In general, the film’s protagonists were willing participants in the documentary.

“They loved it,” says Channells. “They’re all characters and they are all stars. They just loved to have the opportunity to share their story. I think having us there meant they could actually get excited about the [Community Housing Program] – we were part of these new houses that they’d been dreaming of for so long. So they were all really happy to share their stories.”

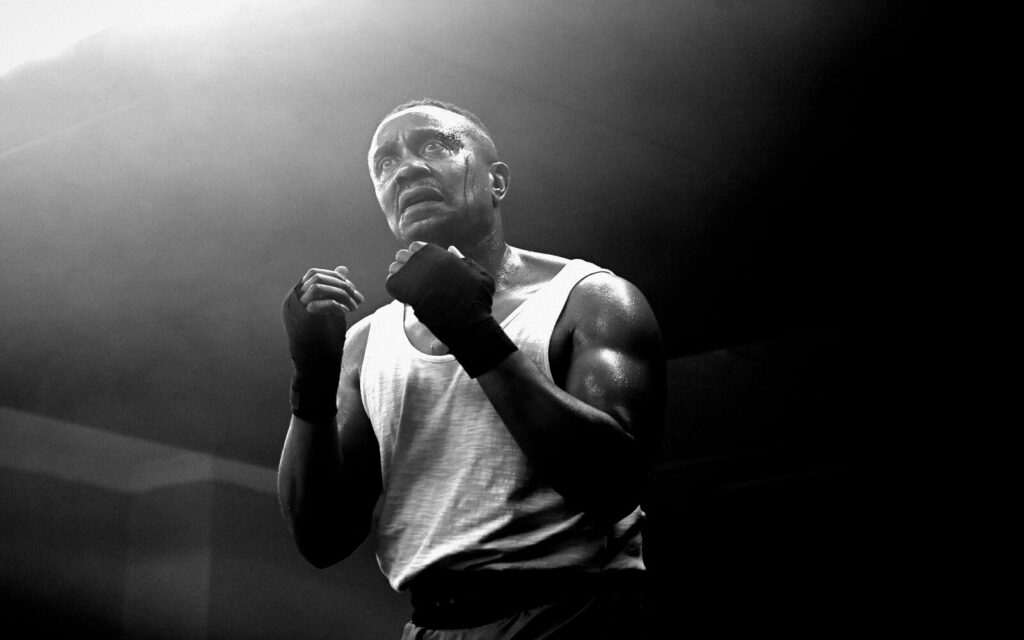

Carolyn, one of the residents at the Oakleigh Centre

The Oakleigh Centre was established in the 1950s. Back then, institutionalised care was considered best practice. Attitudes have evolved with the times, however, and the transition to community housing was a long time coming.

“The proposal to build new homes in the community and move people out of the Oakleigh institution, that had been in the works for at least a decade, maybe more,” says Channells. “So it was really hard for the residents because they’d gotten their hopes up a number of times that they would be moving into new homes that just didn’t eventuate.

“I think this was the third last institution in Melbourne of its kind. So, most of the institutions in their original form have been knocked down and replaced with community housing.”

Given how limited the residents’ relationship with the outside world had been, the transition was both liberating and profoundly transformative. Through Leaving Allen Street, Channells and O’Shea highlight how important it is that every individual be granted the same basic human rights.

“We all deserve freedom and choices and independence and opportunity,” says Channells. “We all have dreams and aspirations and things that we want to achieve in life. We’re in 2020 now – we should be able to support people with disabilities to achieve the things they want to achieve.”

Never miss a story. Sign up to Beat’s newsletter and you’ll be served fresh music, arts, food and culture stories three times a week.