“In short, it’s about this relationship I was in with someone who had a terminal illness,” he says. “We were together for four years before our relationship broke down. The whole record was about that for a long time. In a way, that’s still the thematic foundation, but it extended more to how I was dealing with these things in my life and I had these three guys in my band propping me up.”

The three guys Leaupepe’s referring to are guitarist Joji Malani, bass player Max Dunn and guitar/keys man Jung Kim. The four-piece formed in 2012 and within a few months, FBi were spinning their early demos. Blog reviewers soon caught on, rattling off comparisons to The National and Springsteen on a dreamy day. Then in mid-2013 came Gang of Youths’ first official single Evangelists, which not only received triple j airtime, but also led to a record deal with Sony Music Australia. It’s an enviable trajectory, no doubt, but Leaupepe didn’t set out in search of esteem-boosting plaudits or commercial backing.

“There wasn’t any intention to be a band or to tour or become famous or to make a record,” he says. “I just wanted to hang out with my buds. I’d quit playing music for so long to concentrate on this relationship and being a well-adjusted, well-rounded adult. Then I realised that the healing component and the quality of music that makes us feel whole again was a big part of that.

“The record became more about my buddies propping me up, holding me together after stumbling drunk down the road, throwing up blood trying to figure out my shit,” he continues. “There’s a hugely emotional component related to what we are. I think in most alternative rock bands, it’s a mix-matched bunch of people that met at a share house and make cool music. But as human beings, they were my best friends before we started this fucking thing. They’re the best human beings I know. I’m, in contrast, one of the worst human beings I know.”

The project’s insular and deeply personal nature goes a long way towards explaining why The Positions took more than two years to make. Gang of Youths might be signed to a major label (a true rarity for contemporary Australian rock bands), but Leaupepe was determined to get this thing right, no matter how long it took.

“Sony can’t tell us what to do or when to do it, which is really nice,” he says. “I actually started writing the album in 2012. Then we recorded some stuff mid-2013. The bulk of pre-production was the end of 2013 in New Paltz, New York with Kevin McMahon. That was pre-production and most of the beginning part of the recording, but I’ve been writing the fucking thing for so long that I was recording here and there before that. I like to say that we’ve been working on it for nearly three years.

“It was such a close reflection of the shit that was going on in my life,” he adds. “With a rapidly changing sonic palette, and all the thematic concerns were always in flux. So I felt taking our time with the LP was probably the best approach.”

In virtue of the lengthy lead-up, several album tracks – namely, Knuckles White Dry, Poison Drum, Restraint & Release and Radioface – have already been aired over the last couple years. While it was a long time coming, though, Leaupepe didn’t lose sight of his overarching vision.

“There was a very concerted effort to make the most cohesive record possible,” he says. “It would be a shame to squander three years worth of blood, sweat and tears to come out with this weightless tome of facile garbage. We really wanted to emphasise the cohesion of the record as a body of work, not just a selection of mishmash songs. They’re all about relatively the same shit and there is a non-linear narrative running though the record.”

Along with the thematic content, two other key factors help to disguise the record’s drawn-out preparation. First of all, even if the rhythmic insistence of Restraint & Release is far removed from the orchestral calm of Kansas, Leaupepe’s vocal gravitas holds the spotlight throughout. Secondly, in contrast to the idiosyncratic influence of Leaupepe’s vocals, production-wise, The Positions is a very-polished modern rock record.

“I didn’t want to make some fucking scungy punk, lo-fidelity cliché, inner Sydney-sounding thing,” Leaupepe says. “I talked to the guys. I’m like, ‘I want to fucking reach the stars with this thing. I want to create a record that sounds sonically beautiful and might have broad appeal.’ We’re already influenced by enough old music, so I wanted to create something that’s sonically beautiful, expensive and warm, and can be received by middle-America as well as the gentrified suburbs of the inner city.”

That said, it’s not utterly immaculate. “I’m a punk rocker and metal-head kid,” Leaupepe says. “In my adolescence, I had a taste for Pavement and a taste for Wilco, so I put emphasis on leaving this punk rock energy about it. For example, I used a Dictaphone for a lot of the vocal takes. It was really important that we maintained a sense of our garage roots.

“I wanted to make something that was democratic, not fascist,” he adds. “You know how in Bull Durham, Kevin Costner’s like: ‘Stop throwing fast balls, they’re fascist. Throw more curve balls, they’re more democratic’? I want to throw more curve balls with this one.”

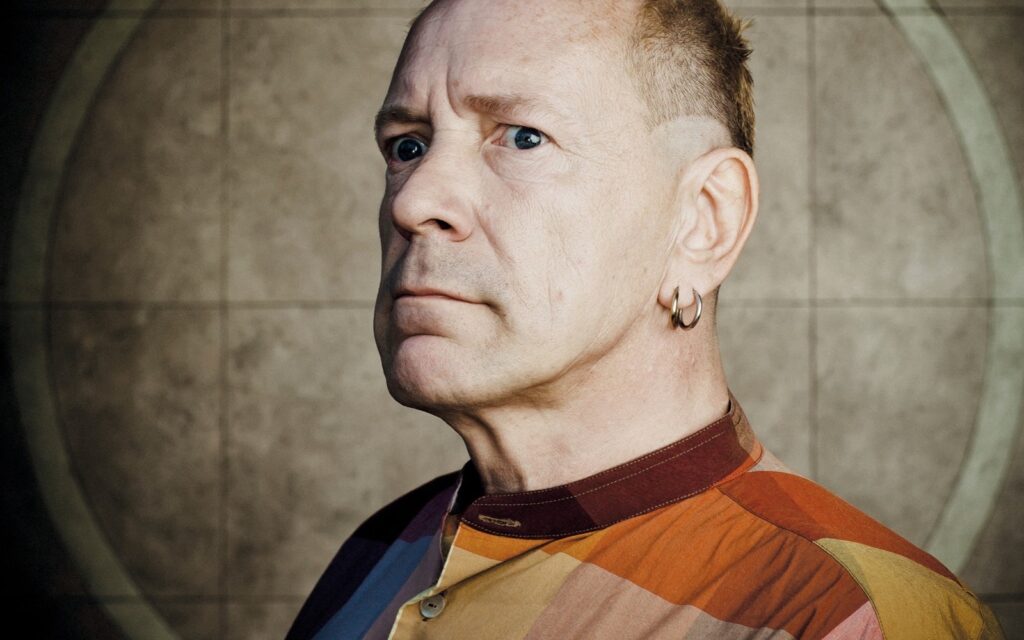

On the subject of fascism, it’s fairly obvious that Leaupepe is Gang of Youths’ unchallenged leader. The tragic personal circumstances that preceded the band’s inception would’ve impacted heavily on anyone, but his leadership seems borderline tyrannical. However, in Leaupepe’s defence, he’s not oblivious to this dictatorial streak.

“I’m an angry control freak on a bad day,” he says. “On a good day, I’m a recalcitrant agitator. For me, this process was so deeply personal I was very reluctant to let anybody in. But they put up with me, they dealt with my moodiness towards my relationship and my self-destructive, addictive behaviours.

“I don’t treat them like plebs as I probably did a couple of years ago when I was so consumed with expelling all this angst and terror that I had in me. But I made no apologies in initially establishing the ground rules. I was like: ‘This is a deeply personal project and I don’t intend for anything to happen with it other than being heard,’ and they still facilitate that. I set parameters initially and they respected them, which has helped me give them a lot more leeway as well. I’ve become more secure in letting them function in their prime responsibilities as best as they can.”

BY AUGUSTUS WELBY