Diving deep into the most significant moments in Australian music festival history.

Music festivals are an important part of the Australian experience, and with the current restrictions on mass gatherings, they’ve been sorely missed in recent times. Whether it’s our endless supply of sunshine, our buccaneer thirst or the fact we enjoy more long weekends than any other nation on earth, there is just something about music festivals that seems to inherently appeal to our Australian sensibilities. With everybody chomping at the bit to get back out there, we thought it was a good time as any to take a walk down memory lane and look back on the moments that shaped the Australian music festival industry.

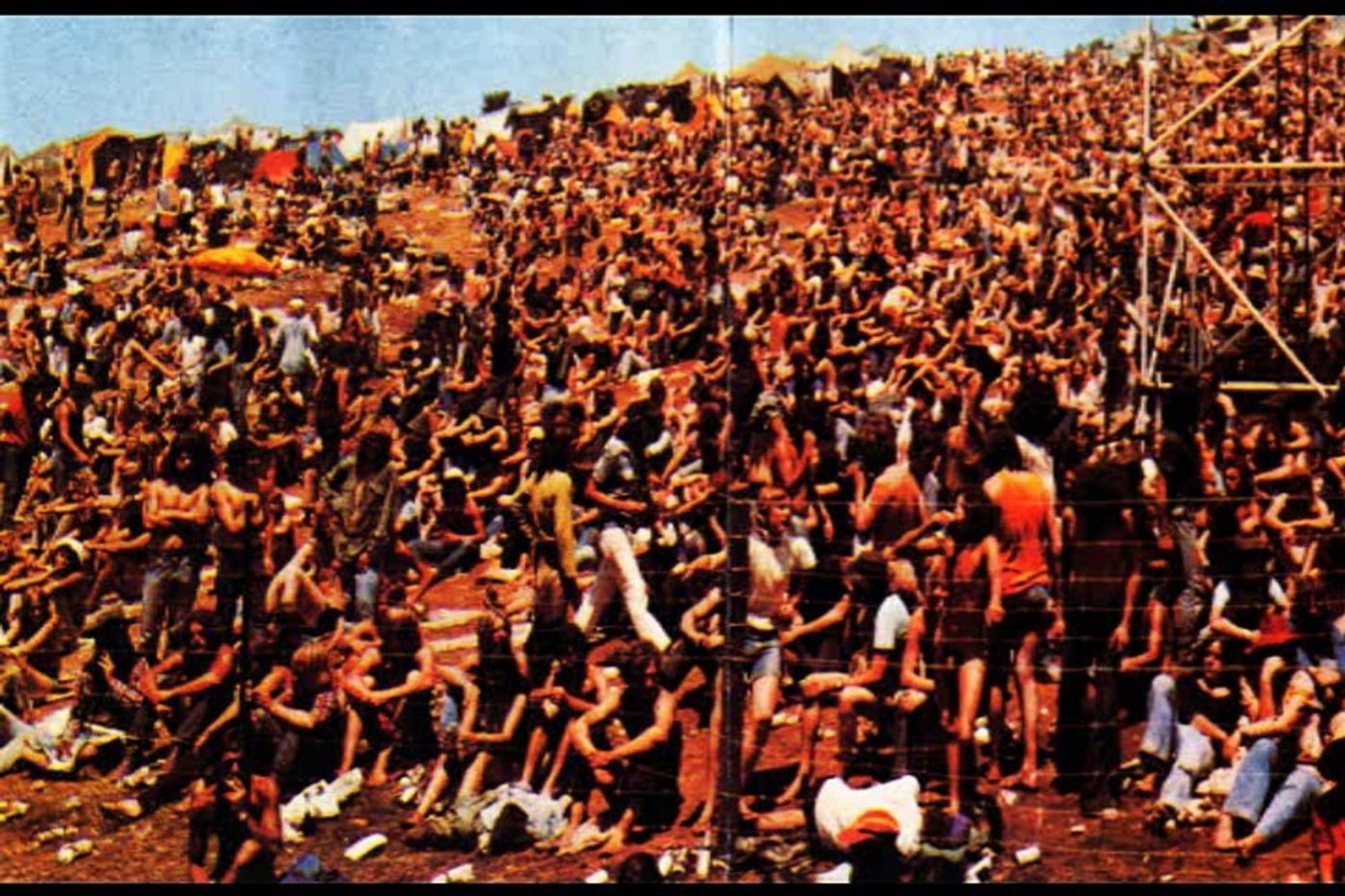

Australia’s First Festival – Ourimbah (1970)

Billed as the ‘Pilgrimage for Pop’, Ourimbah was Australia’s first-ever large scale music festival (a title often wrongly attributed to the ‘72 Sunbury Rock Festival). Taking place only a few months after Woodstock, Ourimbah was in many ways a coming out for Australian youth culture, the so-called ‘young generation’ – hippies and countercultural types who had been at the centre of a lot of bad publicity from the stuffy, conservative media of the ’60s.

Falling on the Australia Day long weekend, the festival saw 10,000 patrons descend on the tiny coastal town of Ourimbah, NSW, with fans treated to sets by local legends like Tully and Billy Thorpe & The Aztecs. Knowing this might be the first and last time a festival like this would be allowed to take place, every precaution was taken to ensure things went to plan. With Altamont festival still fresh in everyone’s minds, a group of Hells Angels were turned away upon entering the township, but other than that, it was basically smooth sailing for the fledgling festival, with Sydney Sun columnist Keith Willey even noting that, “For once the hippies lived up to their reputation for gentleness”.

However, this did not prevent several ‘plain-clothed detectives disguised in casual shirts and sandals’ from making 26 arrests – once again proving that despite the fifty years that have followed, very little has changed in regards to the dicey relationship between festival-goers and the police.

With Ourimbah, a precedent had now been set and Australians had their first taste of the large-scale outdoor music festival and boy, did they like it. The pleasant outcome of Ourimbah meant that for now at least, public opinion was on the side of the young. More permits were greenlit and a small cottage industry began to develop, riding off the positive momentum of Ourimbah. It was very clear that the music festival was well on its way to becoming a national phenomenon.

The Rise (and Fall) of Sunbury – Sunbury Pop Festival (1975)

If Ourimbah was the first Australian festival, then Sunbury can no doubt lay claim to being the most influential. It pulled massive numbers, was the first to present the festival as a recurring annual event and set the blueprint for the ‘festival season’ as we know it. Kicking off in 1972, Sunbury had become the undisputed king of Australian festivals, mostly off the back off blistering sets by local heroes like the Coloured Balls, Billy Thorpe & The Aztecs and Chain. It had grown to become a yearly staple, pushing the limits in everything from general capacity and concession quality to PA size, media access and more. Sunbury was a trailblazer in every sense of the word.

All that would change in 1975, when financial issues would put an abrupt end to the legendary Aussie festival. With poor attendance (mostly due to bad weather) and with mounting performance fees (brought on by an increased reliance on international acts), Sunbury ’75 would be the last hurrah for what had been an amazing run for the local mainstay. Those in attendance remember barnstorming sets from Daddy Cool, The Keystone Angels (later to be renamed ‘The Angels’) and the triumphant return of locals Skyhooks, who just a year before had been bottled off stage by an enraged crowd, who were having none of it.

Despite the stellar performances turned in by the above, little could be done to ease the hellacious rain and as a result, musicians had their hands full trying to get a rise out of a rain-soaked and somewhat despondent crowd. There was tension in the air, and pressure would boil over backstage when a dispute over shared backline between a young AC/DC and UK headliners Deep Purple eventually turned physical, escalating to a point where the Australian band simply refused to go on stage.

When the dust settled, Deep Purple would be the only one of the 23 band bill to see any money from the event, pocketing their $60,000 performance fee (the equivalent $400,000 today) before organisers went into receivership and pissed off the entire Australian music industry, in the process. Eventually the band would do the righty, but the Sunbury ‘75 fiasco would prove an important lesson on the vulnerabilities of the Australian festival circuit, and with new measures being introduced by promotors and bands alike, there was an added sense of professionalism to what had been a relatively cavalier industry up till that point.

Mudbake – Homebake Festival (1996)

With tickets selling like hotcakes, the first-ever Homebake festival was poised to be something of a crowning achievement for the booming Australian music industry of the mid-’90s. Set to take place in the picturesque Belingal Fields on the outskirts of Byron and boasting an all-Aussie lineup featuring a who’s-who of triple j bands of the era, the stage was set for the inaugural Homebake to go off without a hitch. And then it rained… and rained… and rained.

The ensuing downpour turned the once picturesque Belingal Fields into a 15,000 capacity mud pit, with concertgoers hurling handfuls of the nasty stuff, first at each other, then at hospitality workers. The resulting footage makes for some of the most surreal concert viewing you are ever likely to see – not to mention the absolute epitome of 1990s Australia.

While the mud will forever be etched in the minds and clothes of those in attendance, Mudbake will mostly be remembered as the exact moment where Australian music found its niche – taking the graduating class of independent radio and repackaging these diasporic sounds as a united front, one more defined by shared geography than by any generic convention.

The success of Homebake would see a number of copycat festivals pop up over the years, most of which were usually well attended and boasted stellar lineups of new and established Australian talent. This newfound focus on domestic acts would do a lot to galvanise the Australian scene, as well as provide larger international festivals with an incredible talent pool to draw from to help bolster lineups and give rise to the incredibly stacked ‘mega-bills’ of the late 90’s/early 2000’s.

Innocence Lost – Big Day Out (2001)

For much of the ’90s and ’00s, Big Day Out was nothing short of an Aussie institution. The legendary festival had a reputation for consistently treating fans to some of the biggest names in the biz, and in 2001 there were none bigger than American band, Limp Bizkit and their lead singer Fred Durst. Having already expressed concern over the festivals lack of ‘D’ barriers (and given the average Limp Bizkit fans propensity for outdoor bed jumping) there was already a sense of foreboding in the air when the band took to the Sydney stage for the first night of the Australian leg of the tour.

Midway through the band’s nu-metal opus ‘Break Stuff’, the 60,000-strong crowd surged to the front of the stage, trampling one another and spilling over the steel barricades designed to separate band from public. Security staff rushed to retrieve those at the bottom of the melee, but they had their work cut out for them trying to get a handle on the out of control crowd. Durst did his best to try and ease the sea of humanity in front of him, but things deteriorated quickly and before long he was seen hurling expletives and homophobic slurs at the security staff, still unable to contain the situation.

Somewhere amongst all of this chaos, a 16-year-old student named Jessica Michalik is at the bottom of the pack, unconscious due to lack of oxygen in the pit. She would later die from her injuries. Jessica’s death was a perfect storm of preventable circumstances and served as a tragic wake-up call for an industry asleep at the wheel in regards to matters of crowd safety. The public furore and subsequent inquest would result in the implementation of a number of important safety reforms, designed to ensure that nothing like this would ever happen at an Australian festival, ever again.

Australia’s Fyre Festival – Blueprint Festival (2009)

”I’m sorry… I never thought it would turn out like this.” These were the immortal words of Tristan Gray (23), who along with his younger brother Aaron (20) were the brains trust behind Australia’s most infamous festival fiasco – 2009’s disastrous Blueprint festival. On paper, Blueprint had all the makings of a fun weekend away, promising a ‘unique musical experience’ for the 5000 or so punters who descended upon the sleepy town of Ararat (200km west of Melbourne).

Set to take place across ‘two massive stages housed in the region’s natural ampitheatres’ and boasting ‘a gourmet bistro, artisan markets and a craft beer hall’, Blueprint was positioned to be the boutique alternative to the mega-festivals of the late 2000s. Promises of shorter queues, cheaper ticket prices and better concessions were just part of the grand, utopian vision behind the fledgling festival. Unfortunately in practice, things unfolded a little differently and the resultant scenes were some of the bleakest ever witnessed at an Australian festival, leaving punters fuming and creditors out for blood.

Besieged by bad weather in the days leading up to the festival, campers were greeted to ominous scenes from the get-go, as the two natural ampitheatres (a geological formation rarely prized for its drainage) had since grown to resemble two muddy swamps, each leading down to a tiny ‘glorified dome tent’ masquerading as a festival stage. Basic amenities like running water and electricity were also proving elusive for a camp site plagued with every kind of logistical issue imaginable. These power outages would see the two stages whittled down to just one and even then, it was still under construction by the time festivities were set to kick off at 4pm on the Friday. The stage would eventually collapse altogether by the third and final day.

Suppliers had seen the writing on the wall early on and a mutiny was staged in the weeks leading up to Blueprint, severely impacting the festival’s food reserves and rendering the ‘gourmet bistro’ to little more than ‘sub-par tuckshop’. With so few security guards and staff on hand, organisers were forced to limit the number of patrons allowed in the ‘craft beer hall’, thus resulting in long queues and general dissent amongst a thirsty crowd looking to forget the whole experience. Bands also had plenty of time to kill and with the festival running eight hours behind schedule, most of their time was spent backstage – attempting to shoo away the many punters raiding the largely unattended beer supply. With so many infrastructural issues and with the festival unable to recuperate their losses either at the bar or via ticket sales, Blueprint had dug itself into a very deep, very muddy financial hole.

The boys ‘went bush’ and never looked back – fleeing with their tail between their legs and leaving creditors some $500,000 in the red. With the phrase ‘Mum’s backing us’ as their only collateral and with the pseudo-legitimacy afforded by a formal looking letterhead, it was hard to believe that the two rookie promoters even made it this far, slipping through the net and seeing their shaky business plan play out in real life (albeit to disastrous effect). The ensuing comedy gold serves as a kind of cautionary tale for anyone looking to dive into the very real world of event logistics. It’s even used today as a case study to teach Music Industry and Event Management majors how not to run a festival, so at least that’s one positive… I guess.

This article originally appeared in Mixdown Magazine.

Never miss a story. Sign up to Beat’s newsletter and you’ll be served fresh music, arts, food and culture stories five times a week.